Health Must Be Fast-Tracked For 2030

Sep 22, 2023 | Pratirodh Bureau

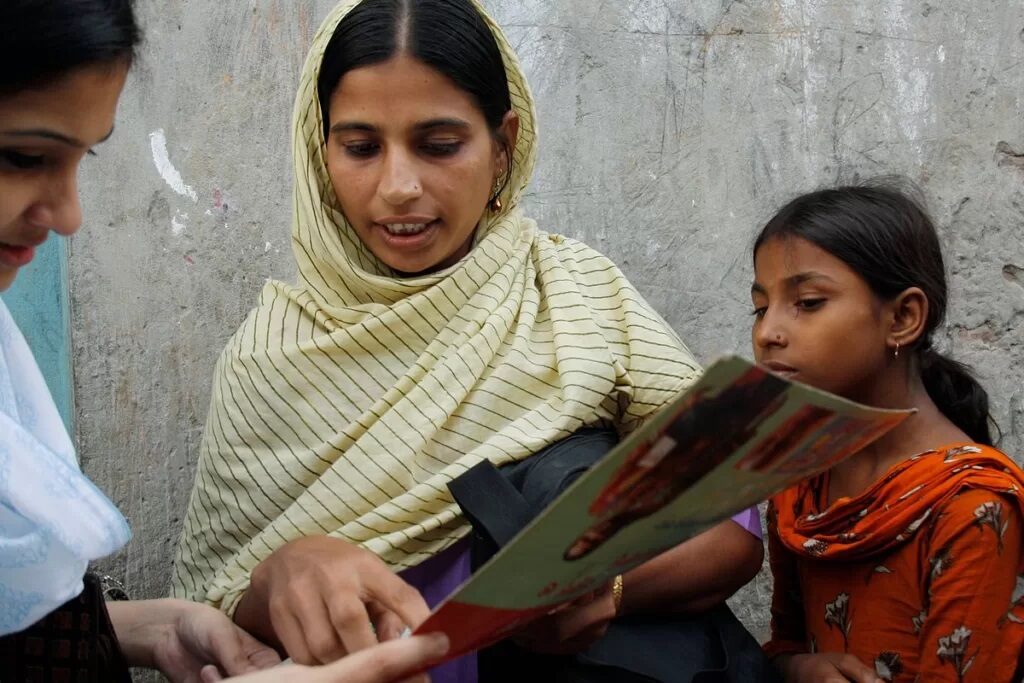

Expansion of the health workforce must be a high priority for SDG targets to be achieved (Flickr: DFID – UK Department for International Development CC BY 2.0)

The COVID-19 pandemic might no longer be a public health emergency but the world is still facing a crisis in health, and progress on Sustainable Development Goal 3 is under threat.

Climate change is bringing an array of health challenges, ranging from severe heat effects and extreme weather events to vector-borne diseases and food insecurity. Antimicrobial resistance threatens to undermine past successes against infectious diseases.

Non-communicable diseases are also increasing, with malnutrition associated with both undernutrition and an expanding epidemic of obesity still to be overcome.

At the halfway point for the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals there is a compelling need to take stock of the progress towards targets, assess the challenges and recommit to achieving the goals.

A meeting in September will do just that and low- and middle-income countries, which constitute the vast majority of the global population, must lead this effort, with support from other nations.

The Sustainable Development Goal 3 on health and well-being for all at all ages was adopted in 2015. It overcame the limitations of the Millennium Development Goals. Three of those eight goals focused on health but still failed to cover many of the world’s major health challenges including non-communicable diseases, mental health disorders, injuries and substance abuse.

Comprehensive primary care, espoused by the Alma Ata declaration of 1978, was cast aside for selective primary care and vertical programmes that were mainly donor-driven. Vertical programmes typically focus on a specific condition or group of health problems and often have only short or medium-term goals.

Universal health coverage was not considered an essential function of national health systems.

The Sustainable Development Goals agenda overcomes these distortions by adopting a life-course approach that gives priority to all major problems undermining health and well-being.

Sustainable Development Goal 3 also identified universal health coverage as the broad platform that could deliver health services while offering financial protection against inordinate out-of-pocket expenditures and debilitating catastrophic health expenditures.

These expenditures were imposed by severe and often acute health conditions that called for hospital care and costly interventions. Their chronic burdens can push people — or sink them deeper — into debt-ridden poverty.

Universal health coverage, when adequately financed and efficiently delivered, offers much-needed protection through high levels of population coverage, service coverage and cost coverage. Affirmation of comprehensive primary care as the lead vehicle of the universal health coverage convoy came as a clarion call in the Astana Declaration of 2018.

Between 2015 and 2019, low- and middle-income countries started working towards the Sustainable Development Goals. However, progress was slow in many countries due to under-resourced health systems, shortages of skilled health workers and a hangover of restrictive vertical programmes still attuned to preset donor priorities.

Yet there have been some successes too. India saw a sharp decline in maternal mortality (from 407 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2000 to 97 during 2018-20). Infant mortality rates halved from 53.6 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2006 to 26.6 in 2023. Under-five mortality fell too. These declines became sharper after the launch of the National Rural Health Mission in 2005.

But health system efforts on newly adopted priorities, like non-communicable diseases and mental health, were still struggling to gather momentum. The burden of non-communicable diseases continued to spiral up, initially in urban areas, but later engulfing rural populations as well. Those trends have continued over recent years in India and other South Asian countries.

The emergence of the COVID-19 pandemic continued to hamper progress towards Sustainable Development Goal 3 targets in low- and middle-income countries. Health system resources were focused mostly on combating and containing the virus and saving lives. Other health services were sidelined or stalled and critical health efforts related to SDGs were deprioritised.

These issues are especially acute in low- and middle-income countries. There are 14 countries in the Asia-Pacific region where maternal mortality rates are higher than the regional average and likely to fall short of the SDG target of fewer than 70 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births by 2030.

A United Nations Population Fund review of 2020 found even higher rates than previously recorded because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Global attention is still on pandemic prevention, preparedness and response, with microbial surveillance and One Health — an approach that recognizes the health of people being closely connected to the health of animals and environments — emerging as major themes of ongoing global health discourse.

Revision of the International Health Regulations and a new pandemic accord are on course for adoption in 2024 under the auspices of the World Health Organization.

Antimicrobial resistance is another looming major public health threat. It is now being packed into the pandemic preparedness agenda, as evident from the outcome document of the G20 Health Ministers’ Meeting in August 2023.

The declaration also recognises the threats posed to health by climate change and calls for climate-resilient and climate-smart health systems.

With seven years left to meet the SDG targets, the world must focus on:

- primary care-led universal health coverage;

- multi-sectoral actions across other SDGs to steer policies and programmes that will enable and not erode overall health;

- active engagement of communities in all stages of health policies and programmes;

- increasing global access to technologies that can protect, preserve and restore health — such as vaccines, diagnostics and drugs — without being hampered by profit-hungry, patent-restrictive practices; and

- research and innovation that can identify and evaluate new methods to improve health system performance, such as digital technologies.

These call for increased national and global financing for health systems and health-related multi-sectoral actions. It is futile to think of financing for health security that is defined only in terms of acute events.

Since population health is the best overall indicator of success across all SDGs, global policymakers must give more funding to the health sector and health-relevant programmes in other sectors.

Improved governance measures need to also ensure efficiency gains for money spent.

Expansion of the health workforce must also be a priority. A recent estimate indicates that a 15 million shortage in the global health workforce in 2020 will reduce to 10 million by 2030 but with much slower progress in the WHO’s African and Eastern Mediterranean regions.

But there is great danger that high-income countries with ageing populations will increasingly recruit health workers from low- and middle-income countries, weakening the latter’s health systems. High-income countries must co-invest with low- and middle-income countries to educate and train the health workers in those countries.

While health workforce expansion must involve all categories of health workers, the greatest attention must be paid to those needed in primary care, which is pivotal to achieve Goal 3 targets.

There is sufficient global evidence on the impactful and equity-promoting capabilities of community health workers in improving maternal and child health, non-communicable diseases, mental health and pandemic response.

We need to scale up and skill up this transformational component of the health workforce.

One can only hope that the policymakers, international organisations and development partners meeting in September 2023 to review progress on the SDGs will take the necessary steps to make this commitment.