Confronting Himalayan Water Woes Before It Is Too Late

Feb 3, 2023 | Shalini Rai

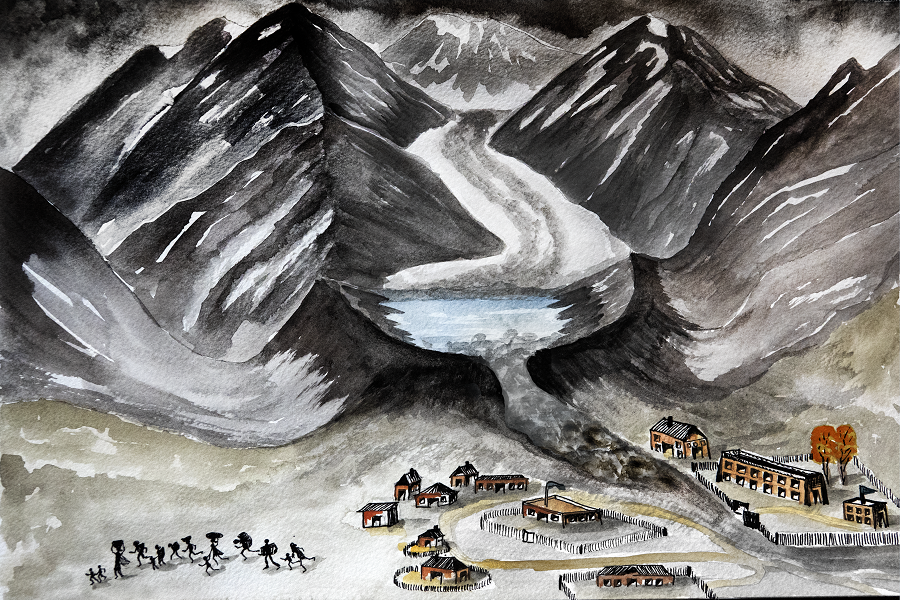

Rising temperatures, unchecked urbanisation and commercial greed are melting glaciers and other frozen water across the Himalayas. Urgent action is needed to secure water supplies and prevent disasters in the region (Illustration: Arati Kumar-Rao)

Last week, Ladakh-based maverick climate activist Sonam Wangchuk went on a 5-day fast to raise awareness about receding glaciers and the high cost of proposed ‘development’ projects in the high-altitude desert region.

Wangchuk, who is reported to have inspired the character played by Aamir Khan in the film ‘3 Idiots’, began his five-day climate fast on January 26, to attract the Centre’s attention to the demands of the Ladakhi people. Originally scheduled to be organised at Khardung La, one of the highest motorable passes in the world, Wangchuk had to acquiesce to hold the fast at the Himalayan Institute of Alternatives, Ladakh campus, set up by him, when he was denied permission by the Union Territory administration.

Among Wangchuk’s demands were extension of the Sixth Schedule of the Constitution to Ladakh and protection of the environment from unchecked industrial and commercial expansion in the Union Territory. He had been categorical that environmental protection is of utmost importance in Ladakh as two-thirds of the glaciers in the region are extinct.

These developments took me back to my sojourn in Manali, Himachal Pradesh, over a decade ago and reminded me of the water scarcity and related issues I encountered back then — a glaring example of the similarity of climate challenges across the Himalayas.

When I was there, the town of Manali and surrounding areas were dependent on their water needs on the major rivers Beas and Manalsu and on smaller glacier-fed streams. The water supply in Old Manali, where I lived, was erratic at best and would fall to critical levels during the ‘peak’ tourist season. In winters, the water would simply freeze in pipes.

There was one water tank of 1000 litre-capacity on the roof of the single storey, two-room structure we called home and it would be an occasion for celebration for me and my housemate if it became ‘full’ on its own (when there was enough water and enough water pressure to fill up the tank).

Most of our days were spent worrying over low water levels in the tank overhead. There would be no water to wash utensils, to bathe and clean the house. For drinking water, we relied on packaged water bottles.

It did not help that tourist activities went on unchecked in the area and in the name of ‘development’, glaring violations of environmental norms were carried out.

This scenario is repeated in tourist towns across the Himalayas and needless to say, is cause for concern. On one hand is the already existing and steadily worsening problem of a warming climate and erratic weather leading to plunging water levels. On the other is the haphazard, unauthorized, ill-planned urbanisation of Himalayan towns and hamlets, with no planning to provide adequate water and sewerage facilities.

This bodes ill for both the year-round residents and for ‘peak’ tourist season visitors. Already, there are reports of muddy water spewing from taps in Manali. Soon, there might not be any water available.

Activists, including Wangchuk, have tried to raise awareness about the consequences of water scarcity for not just Ladakhis but populations downstream, including a large part of north India. In this context, the Ice Stupa Project in which he was involved, is a seminal achievement by the people of Ladakh. It could even be replicated in areas with similar topography and terrain and could prove to be of critical help in watering fields in the spring and meeting other water needs of the community.

In April 2021, Roxy Mathew Koll, a climate scientist at the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology, Pune, told Mongabay-India that the snowfall rate has decreased across the Himalayan region in past several decades.

“…the recent climate change assessment report for India shows that the temperature over the Himalayas is warming due to climate change, at a rate of 0.2 degrees Celsius per decade. At high elevations (above 4000 m), the warming rate is up to 0.4 degrees Celsius per decade. This has led to a significant melting and decline in glacier mass over the Himalayan region in the recent decades,” he said.

“Monsoon rainfall already shows a decline over the Indo-Gangetic plains, due to climate change. So, a decrease in glacier-fed flow downstream can result in an aggravated water stress for downstream communities. We need to be prepared to address such a situation,” he added.

The impact of low snowfall and rainfall in HP is seen in record dipping of water level in reservoirs of the Bhakra dam and the Pong dam, that are situated over the Beas and Sutlej rivers, that originate in Himalayan ranges. The water level in the Pong reservoir is critically low and the refilling season does not begin before the monsoon arrives in June. This hits drinking water and electricity supply.

Water flows to Rajasthan, Haryana and Delhi for drinking purpose from the Pong reservoir. And owing to the dip in water level, power generation in Bhakra dam too gets reduced to half.

We ignore these scenarios only at our own peril. While it might appear that the situation is irreversible, it is still not too late to preserve water, ration its supply and optimise its usage in the Himalayas. Also important are adequate checks on rapid ‘development’ and urbanisation, in addition to awareness campaigns for the public and other stakeholders.

Water really is the backbone of any human settlement. History is awash with instances of entire empires and even civilizations collapsing due to water paucity. It will be a sad day indeed if this preventable tragedy is allowed to take place in our backyard — the magnificent Himalayan towns and cities.