Reading The Aravallis Through Maps And Law

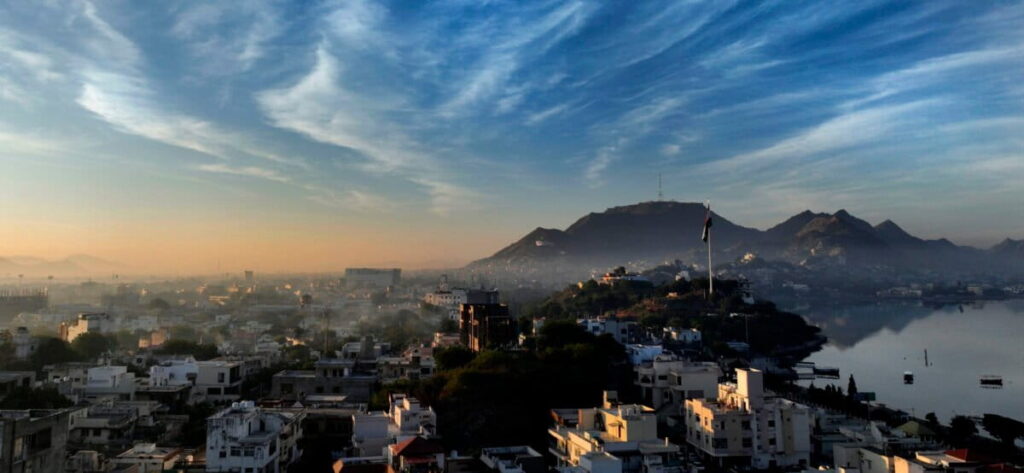

The Ana Sagar lake in Ajmer, Rajasthan, against the backdrop of the Aravalli mountain ranges (AP Photo/Rajesh Kumar Singh)

- A spatial analysis across Aravalli states shows profound consequences of reframing the definition of what counts as a hill and range in one of the world’s oldest mountain systems.

- In Rajasthan, over 70% of the current Aravalli extent would lose protection with the new definition, if passed. In Gujarat and Haryana, the figure rises to about 82%. In Delhi, the entire Aravalli extent falls below the elevation cut-off unless protected under separate instruments.

- Additionally, nearly 41.8% of the natural vegetation in Rajasthan’s Aravallis, including two-thirds of the state’s savannah grasslands, all of its sand dunes and 18.35 sq. km. of its forests are at risk.

Across western and northern India, the Aravallis appear in fragments: a rocky ridge at a town’s edge, a grazed grassland, a seasonal stream, a low dune system holding the desert in place. Individually perhaps unremarkable, but together they form one of India’s most important ecological systems: open natural ecosystems (ONEs). Many of these landscapes are also embedded in cultural and religious traditions, encompassing orans, sacred groves, and Vedic river systems such as the holy Saraswati.

Yet, this vital geography recently faced an existential threat.

On November 20, 2025, the Supreme Court of India adopted a definition proposed by the Central Government that limited the Aravalli ‘Hills’ to those rising more than 100 meters above the surrounding land and the ‘Range’ to two or more such hills located within 500 metres of each other. Though framed as a technical clarification, the rule redraws the landscape by excluding significant terrain from protection.

However, the legal tide has since turned. After staying its own order in December 2025, the Court on January 21, 2026 extended the stay further. The Bench directed the Additional Solicitor General and the amicus curiae to suggest names of environmentalists and scientists with expertise in mining and related fields. This would result in a court-supervised expert committee to assist it with ongoing proceedings.

The immediate danger may have been put on hold, but the question of implications of the definition remains.

A spatial analysis by researchers from the Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE), across Gujarat, Rajasthan, Haryana, and Delhi show profound consequences that could occur due to this reframing.

Mapping the definition onto the land

The analysis focused on thirty districts identified by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) under the Aravalli Green Wall Project, currently one of the most detailed publicly available government delineations of the range.

The team examined elevation profiles for 27,638 villages across this landscape. Elevation in these districts ranges from 0 to over 1600 metres above mean sea level.

For each village, the difference between its highest and lowest elevation points was calculated, directly reflecting the Court’s instruction to limit the Aravallis to hills rising more than 100 metres above their surroundings.

When this rule is applied across the region, almost 80% of the villages surveyed, which is over 22,000 villages, covering more than 107,000 square kilometres, fall below the threshold. This is larger than all of Punjab and Himachal Pradesh, put together.

In Rajasthan, over 70% of the current Aravalli extent would lose protection. In Gujarat and Haryana, the figure rises to about 82%. In Delhi, the entire Aravalli extent falls below the elevation cut-off unless protected under separate instruments.

Adding ecosystems to the map

To understand the ecological consequences of this reclassification, the elevation results were overlaid with ONE maps. These maps identify natural ecosystems such as savannah grasslands, shrublands, woodlands, dunes, wetlands, saline flats, forests, and rocky or sparsely vegetated systems found in these districts today.

We estimate that nearly 41.8% of the natural vegetation in Rajasthan’s Aravallis, including two-thirds of the state’s savannah grasslands, all of its sand dunes and 18.35 sq km of its forests are at risk of losing protection. Similar losses are likely to occur in Haryana’s Aravallis (41.2%) and Gujarat’s Aravallis (32%).

All of the natural vegetation and hills in the Delhi Aravallis are at risk of losing protection. For a city facing persistent water stress, severe pollution levels, and rising temperatures, retaining functional protection for the Ridge is central to long-term resilience planning as it provides all of these ecosystem services naturally.

Landscapes of use, not emptiness

It is important to recognise that even low-relief savannahs, scrublands, dunes, and wetlands across these regions are working landscapes, not residual or vacant land. For pastoralist, Adivasi, and agro-pastoralist communities, these ecosystems sustain grazing, seasonal mobility, fodder systems, and shared water sources that have evolved over centuries. In Haryana and Delhi, almost all water/wetland areas will be delisted. This would have significant impacts for communities in the area.

Regulatory frameworks would need to explicitly acknowledge these uses by retaining protection for commons such as grazing grounds, johads, wetlands, and seasonal routes, even where elevation thresholds are not met. Recognising customary access and seasonal use within land classification systems can help ensure continuity of livelihoods and ecological stewardship. Including this within planning and mineral governance frameworks can reduce cumulative impacts that often go unrecorded in official data.

Where landscapes are delisted or reclassified, safeguards would be required to prevent automatic expansion of mining, infrastructure, real estate development, and land conversion. This would include social impact assessments, scrutiny of effects on commons, and consultation processes that account for pastoral mobility rather than only settled land ownership. Integrating community use into conservation and land-use policy is therefore essential to sustaining both livelihoods and landscape resilience.

The dune belt and the edge of the desert

Dune systems along the eastern edge of the Thar Desert form a broad, low-relief transition zone between arid and semi-arid landscapes. While most dunes here are inherently mobile and shaped by wind, the Aravalli range plays an important regional role in moderating desert expansion by supporting vegetation, soil stability, and hydrological systems that reduce wind erosion and limit large-scale sand movement.

The spatial analysis shows that Rajasthan and Gujarat stand to lose all of its legally protected dune ecosystems under the new definition. Almost all saline flats will also be lost in Rajasthan and Gujarat.

Retaining regulatory recognition for dune belts would be critical to limiting disturbance in this transition zone. Managing these landscapes as erosion-control and desert-buffer systems would help maintain their role in moderating sand movement and reducing the long-term risk of desert expansion towards the northern plains.

When redefinition stymies policy goals

The spatial patterns revealed by the analysis point to the need for closer alignment between land classification rules and ongoing public investments in ecological restoration.

Large government programmes aimed at reviving the Saraswati river system, which spans multiple states, would benefit ecologically and monetarily from regulatory definitions that retain protection for paleo-channels, wetlands, and shallow aquifers in the Aravalli foothills and by aligning elevation-based classifications with hydrological mapping.

A similar coordination is required for the Aravalli Green Wall Project, which costs over ₹160 billion. Designed as a 1,400-kilometre ecological buffer against desertification, the project depends on low-relief districts that spatial overlays identify as most affected by recent delisting. Reconciling land-use reclassification with the project’s ecological and monetary footprint would help preserve the terrain necessary for its long-term viability.

Afforestation and restoration initiatives, including compensatory afforestation, would benefit from implementing an ecosystem approach instead of uniform tree-planting targets. Integrating grasslands, scrub, wetlands, and recharge zones into planning frameworks can improve ecological outcomes and promote efficient use of public funds.

Taken together, these patterns underline the case for a coherent grasslands and open ecosystems policy that recognises landscape diversity, aligns restoration spending with ecological function, and balances the needs of communities, water security, and long-term land stewardship.

Balancing mineral development and ecological integrity

Read alongside maps, the 100-metre elevation rule that excludes vast landscapes coincides with a wider set of regulatory shifts in mineral extraction.

The first of these regulatory shifts is in the Supreme Court’s order which includes specific exemptions, allowing new mining leases to be granted for minerals including atomic, critical and strategic minerals. The minerals covered under these exceptions can be mined even with other restrictions in place.

Second, in a separate matter decided days earlier, the Court allowed the grant of post-facto environmental clearances, enabling regulatory approval to be issued after project activities have already commenced. This introduced an additional procedural pathway within the environmental clearance regime.

In parallel, draft amendments to the Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act, 1957 propose removing existing limits on the maximum area of mineral concessions that may be held by a single person within a state, potentially allowing larger consolidated holdings.

Third, the passage of the SHANTI Act (Sustainable Harnessing and Advancement of Nuclear Energy for Transforming India Act, 2025) in December 2025 marked a change in nuclear sector policy by permitting private participation for the first time since 1962, while reducing their liability in nuclear accidents. Uranium- and thorium-bearing minerals, classified as atomic minerals and explicitly exempted in the Aravalli judgment, fall within the scope of activities enabled under this policy framework.

Taken together, these developments highlight the need for clear regulatory guardrails around strategic mineral extraction and overall protection of the range. The court-mandated Management Plan for Sustainable Mining (MPSM) framework must remain firmly anchored in ecological health assessments, cumulative impact studies, and inclusive public consultation, even when projects are framed in terms of national interest or energy security. Defence or security classifications, when invoked, require defined limits and dependent oversight.

Without this, the consolidation of access to critical minerals risks creating regulatory gaps where environmental harm and unauthorised mining can occur beyond public view, even by non-state actors. Strengthening oversight mechanisms is therefore central to aligning strategic resource extraction with long-term ecological integrity and public accountability.

What the analysis tell us

This analysis clarifies how technical rules shape land governance in practice. When steepness becomes the primary criterion, landscapes that are ecologically complex but topographically simple are more likely to fall outside regulatory oversight. What remains protected is easier to measure and administer, while systems that sustain water flows, grazing economies, and long-term resilience risk being overlooked.

The implications will emerge gradually. They will be felt through changes in access to commons, pressures on aquifers, disruptions to grazing routes, and increased instability along desert margins. These effects are cumulative and often difficult to reverse once land classifications shift.

The maps, therefore, point to a practical lesson. Legal definitions work best when they reflect ecological function as well as form. Retaining space within regulatory frameworks for low-relief ecosystems, community-managed landscapes, and hydrological systems would help ensure that protection keeps pace with how these landscapes actually work. Doing so is less about expanding regulation than about aligning law, science, and lived use, so that decisions taken on paper continue to support resilience on the ground.