Privacy Concerns Rise As Wildlife Surveillance Tech ‘Watches’ People

Aug 9, 2023 | Pratirodh Bureau

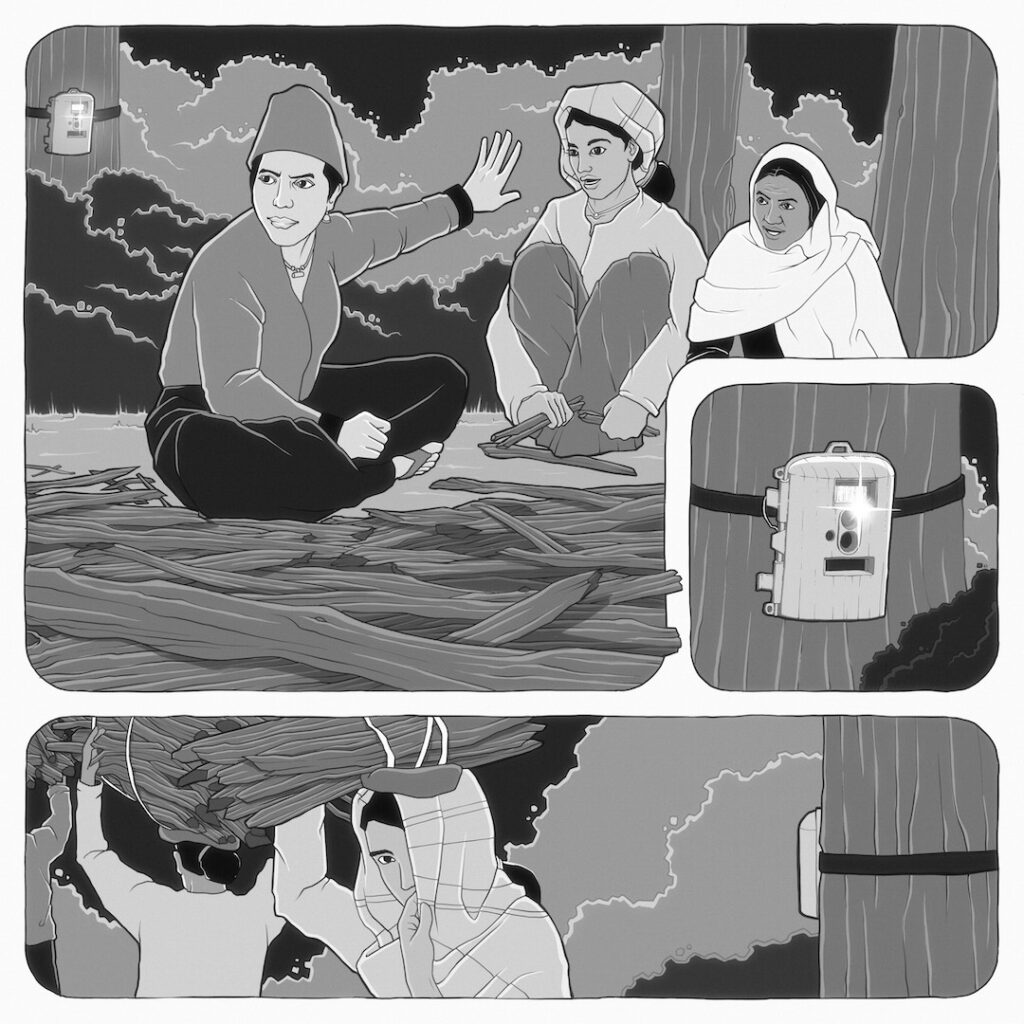

Women in forests feel wary when camera traps are around (Illustration by Adwait Pawar and Trishant Simlai)

In 2017, a camera installed on the fringes of Corbett Tiger Reserve in northern India photographed an unsuspecting woman.

The local forest staff had set up the device discreetly to monitor passing tigers and elephants. But residents of a nearby village, which lacks toilets, also used the same area the camera was watching. Oblivious to the device, the woman had entered the camera’s field of view while squatting to relieve herself. A forest guard and a couple of forest watchers later shared her pictures on local WhatsApp and Facebook groups. What was meant to be a private moment turned into a public spectacle.

“It was like a joke, but it became a major case of sexual harassment,” says Trishant Simlai, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Cambridge’s Department of Sociology. “It didn’t become a bigger issue because the forest watchers were from the same village. But the camera trap ended up being used for something it wasn’t meant for.”

This wasn’t an isolated incident, Simlai found during the 14 months he spent in and around Corbett Tiger Reserve (CTR) for his Ph.D. In one of the first studies of its kind from the Global South, Simlai was trying to figure out what happens when technologies meant for conservation watch people instead.

After all, various technologies — from camera traps to drones and acoustic sensors — help researchers, conservation groups and governments keep a watch on wildlife and the places they inhabit. Some of the technologies have even transformed how we track animal movements, estimate their populations, and figure out what threatens their survival. But these technologies also end up watching people who use the same landscapes as wildlife, capturing their photos, videos, and voices, often without their knowledge.

Some of this footage may be innocuous. But it can also lead to precarious situations. Like in Austria in 2012, when a hidden camera set up in a forest snapped a local politician having sex, making him eligible for up to 20,000 euros ($22,000). In fact, many scientists who’ve set up camera traps in Africa, the U.S. and Asia have found “private” images of people who are naked, dancing or defecating. Several researchers have also seen images of local people engaged in what they deem to be “illegal activities.” At the same time, conservation surveillance technologies have posed a threat to researchers themselves, and to their work. In Iran, for example, a group of cheetah researchers using camera traps were charged with jail terms when they were suspected of espionage. Researchers globally have also had their camera traps stolen and damaged, and their drones shot at.

Still, despite conservation surveillance technologies frequently capturing footage of Indigenous and local communities, accidentally or intentionally, very few researchers have looked at how these tools actually impact the people who get watched.

This “human bycatch,” researchers like Simlai caution, can have serious ethical and social implications.

The Gaze Of Cameras

Let’s take camera traps, for instance. These cameras with motion sensors, which are triggered whenever an animal or a person crosses their path, are now routinely used by scientists, governments, hunters and wildlife enthusiasts across the world to monitor wildlife remotely.

In fact, it’s thanks to camera trap data that Corbett Tiger Reserve is estimated to have one of the world’s highest tiger numbers. “This has completely changed the value the tiger reserve holds,” says Rajiv Bhartari, the former principal chief conservator of forests and chief wildlife warden of the state of Uttarakhand, where CTR is located. Now, camera traps are routinely used to count tigers, identify “problem” individuals that may have attacked a human, and to find other threats in the forests.

These conservation goals still exist for camera traps, Simlai says. But the cameras are installed not just in the core areas of the park; they’re also in the buffer zones, where some human activity is allowed. So the devices also opportunistically photograph people. This has complex social and ethical consequences, which are disproportionately graver for women and people from marginalised communities, Simlai found during his Ph.D. research.

Local women, for instance, often venture into the forests, legally, to collect firewood, grass, and other nontimber forest produce. “They call the forest their maika [maternal home],” says Munish Kumar, a local social activist with the Samajwadi Lokmanch public advocacy group near CTR. “It is where they share stories about their lives with each other.”

Nobody seeks the women’s consent or tells them where the cameras are, Kumar adds, but someone might spot one, and word spreads around.

The very idea of camera traps in the forest — usually controlled by male forest staff who sometimes embellish the capabilities of the devices as being able to “watch and hear everything” — instills a sense of fear among many women, Simlai found. Some women change how they behave in the forest as a result, like avoiding loud conversations or songs, which is also a way for them to warn wildlife about their presence. Some change the way they dress. Others go to unfamiliar forested areas to avoid the devices altogether, increasing the risks of dangerous wildlife encounters. At the same time, many local men view camera traps positively, Simlai says: “Because women spend less time in the forest and come home sooner.”

Those in power also use “human data” from camera traps in problematic ways, Simlai found. Pictures from camera traps have led to cases of voyeurism and sexual harassment, for instance, like in the case of the woman snapped while relieving herself. She was both autistic and a Dalit, while the forest guard who shared her picture belonged to a privileged caste.

Camera-trap images have been used for moral policing, like an instance where a picture of a couple from a local village was reported to the police. Simlai also observed one forest officer pause at a camera trap image of two men from a marginalised community and profile them as “criminals” based on how they were dressed, despite the staff informing him that the forest department itself had hired the men to dig a canal inside the forest.

“Technology gives you increased power, but it depends on the person, how they use it,” Bhartari says. “Still, in Corbett, I think camera traps have been used more for good than the not-so-good reasons.”

But the lines between good and not-so-good can blur quickly.

Ethical Dilemmas

For Koustubh Sharma, camera traps have been a gamechanger. “The kind of data, natural history information, and the kind of understanding we’ve got about wildlife in the last 25 years because of camera traps, it’s absolutely unparallelled,” says Sharma, science and conservation director of the Snow Leopard Trust, a nonprofit conservation organisation that works across 12 countries.

In every place they’ve set up cameras, Sharma and his colleagues have been careful to explain to the local residents how the devices work, and what they can and cannot do.

“There have been incidences where people were worried that camera traps placed up on the mountains could look into their homes further down,” he says. “So we showed them the images from the cameras, and they became comfortable that the cameras weren’t snooping into their homes; that the devices have a very narrow field of view, with very specific capability.”

Still, a few incidents made the researchers think more deeply about the ethical dilemmas of using camera traps. For example, in separate instances in Mongolia and Kyrgyzstan, their camera traps had snapped men carrying guns through areas where hunting wasn’t permitted; in Kyrgyzstan, this even led to the community losing its annual conservation bonus, a considerable amount. The researchers were bound by local laws to hand over the images to the authorities. “But it concerned us: Did this person really have sufficient warning to not carry the gun in that area? Had we explicitly informed them what the consequences would be?” Sharma says.

Meanwhile, the researchers were noticing another trend. More and more scientists, and conservation groups around the world were using camera traps to investigate poaching and threats to wildlife, using pictures of humans as a proxy for “threats.”

“There’s nothing wrong in using camera traps as antipoaching tools,” Sharma says. “But then you need to follow similar guidelines as are followed for CCTV or for other public surveillance tech: you need to warn, you need to give people enough opportunity to not commit the crime if the surveillance is to be used as a deterrent.”

Unlike public surveillance technologies, though, ethical guidelines don’t yet exist for conservation technologies. This is despite some conservation projects having historically been coercive and violent, particularly affecting marginalised and Indigenous communities. “And then we are adding technological tools to make it even more difficult for the communities,” Sharma says.

So, in November 2020, Sharma and his colleagues published a paper outlining a checklist of best practices that can minimise harm to both communities and researchers. These include seeking consent from communities where they have jurisdiction; having extensive and regular conversations with the people who use public lands or protected areas about what the cameras are being set up for, and what they’re not; understanding the local laws of using the technology; and explaining the legal consequences of being photographed to the local communities. In addition, they urge researchers to clearly spell out the purpose of their study in advance, and not use human images opportunistically.

It’s not just camera traps. Researchers are calling for more responsible use of numerous other conservation surveillance technologies that can also potentially harm people.

World Of Surveillance

Take drones, for example. These unmanned aircraft, usually fitted with high-resolution cameras to record photos and videos, offer a unique aerial perspective. This has transformed what researchers can do, such as counting threatened animals more reliably, finding rare plants, monitoring changes in forests and oceans, and tackling forest fires.

At the same time, drones are becoming increasingly popular as a solution to poaching. In fact, law enforcement authorities in several protected areas in Asia and Africa are using drones to specifically surveil people’s movements. But in the quest to catch poachers or curb illegal activities, some researchers worry that drones, too, might harm the local communities if used without ethical deliberation. Drones could be used to stereotype certain vulnerable groups of people as criminals, infringe upon residents’ privacy, create a climate of fear, and feed hostility among the people who are being watched. These consequences can then further alienate local communities and harm conservation in the long term, researchers say.

In Corbett Tiger Reserve, for instance, Simlai found that the men in charge of operating the drones, all of them from privileged castes, neither flew the drones based on any scientific rationale, nor surveilled every village equally. Before flying drones over villages with people mostly from privileged groups, for example, the drone team would get permission from the village headman, Simlai observed. The team would also take his advice on where to fly the drones — like whether there had been any movement of animals in the area, or if any “suspicious” people had recently arrived.

But the drone operators wouldn’t seek similar consent from villages with people mostly from marginalised communities. On the contrary, the team would appear in these villages unannounced and sometimes even actively spread misinformation about what the drone could do, such as saying the drones had facial-recognition abilities and were linked to people’s ID cards. This was done, some forest staff told Simlai, to create an “atmosphere of terror.”

There are bigger questions, Bhartari adds, like whether these technologies are the best use of limited resources. After all, many protected areas around the world suffer from staff shortages and funding crunches.

“We keep increasing the number of equipment without increasing the manpower that can use the technologies and have the skills to analyse what they are capturing,” Bhartari says. “I’m also worried about the safety of the expensive equipment themselves. How do you ensure they’re not stolen, damaged and misused?”

Some researchers also worry that the footage from conservation technologies might be skewing how the general public views landscapes. This is partly because conservation groups and authorities often select the most “pristine” images from their sites to showcase to the public. Even popular wildlife feeds that livestream lions, elephants, bears or moose don’t feature people, says Erica von Essen, an associate professor at Stockholm University’s Department of Social Anthropology. “And it gives this impression that wildlife exists separately from communities,” she says. “In the livestreams of polar bear migrations and moose migration, which we have here in Sweden, people absolutely do not want to see wires, vehicles, or people.”

The increasing reliance on technologies can also distance protected-area rangers themselves from on-the-ground realities. “One of my biggest challenges was how to make sure that forest officers go to different areas on foot and talk to people,” Bhartari says. “You can use photos or videos from technologies to create an impression that you’re surveying your area, that you’re knowledgeable. But in reality, you’re not.”

In short, all conservation surveillance technologies can have complex social and ethical impacts. Recognising that such technologies are only proliferating and becoming more powerful at processing data, thanks to millions of dollars being poured into their development, Simlai and his colleagues published a paper in 2021 laying out some guidelines for more responsible use of tech.

Responsible Tech

Like Sharma’s guidelines for camera traps, Simlai and others argue that researchers should not just be transparent and upfront with people about how their technology will be used, but also how the data will be protected, and who gets to use it. More importantly, they urge researchers to evaluate who benefits from the tech and who gets harmed; and deploy the tech only when there are no alternative, less-intrusive ways of collecting the data. It’s particularly important for researchers to critically assess their technology, Simlai says, since they are the ones who often introduce new tech to protected areas, which the park authorities then use.

These conversations are beginning have an impact. The conservation science journal Oryx now includes both of these guidelines in its ethical standards for authors, becoming the first journal to do so. This is a step in the right direction, Sharma says, because unlike many other forms of human data, such as medical or socioeconomic data, human bycatch from conservation technologies have so far remained unaddressed. Sharma says he hopes more journals will follow suit. “It’ll only make research easier, keep researchers safer, and make the technologies less threatening to communities.”

Some conservation researchers, though, say guidelines such as seeking consent from local communities are moot, especially when technologies are used outside protected areas. “The calls for consent are a cosmetic attempt to ‘cleanse’ an illegal intrusion,” says Mordecai Ogada, a carnivore ecologist and conservation writer from Kenya. “There is no human who will consent to a camera being placed around his home area by strangers.”

In lands that are owned by communities, Ogada says, researchers shouldn’t use surveillance technologies like camera traps at all. “Conservation scientists never use camera trap information for the benefit of local people. It is invariably used to vilify them.”

However, many Indigenous peoples and local communities (IPLCs) worldwide are now using conservation surveillance technologies themselves to protect their lands, prevent illegal activities, and strengthen their autonomy. Communities in South America, like in the Brazilian and Peruvian Amazon, are using drones to monitor forest fires and record illegal miners and loggers. Similarly, communities in Indonesia are using drones to map their lands and challenge land grabs.

No matter who uses the technologies, it’s important to question the social and ethical consequences of the tools through the perspectives of gender, class, caste and so on, Simlai says.

This is especially important as global commitments to protect biodiversity increasingly call for recognising and protecting the rights of Indigenous and local communities. “There is greater understanding of the need to involve communities in conservation,” Sharma says, “but it is more important to do it the right way.”

(Published under Creative Commons from Mongabay-India. Read the original article here)