Obama Says Gandhi’s Writings Gave Voice To His “Deepest Instincts”

Nov 17, 2020 | Pratirodh Bureau

Kalicharan Maharaj also made several claims and allegations against Mahatma Gandhi and held him responsible for “encouraging the Nehru-Gandhi dynasty”

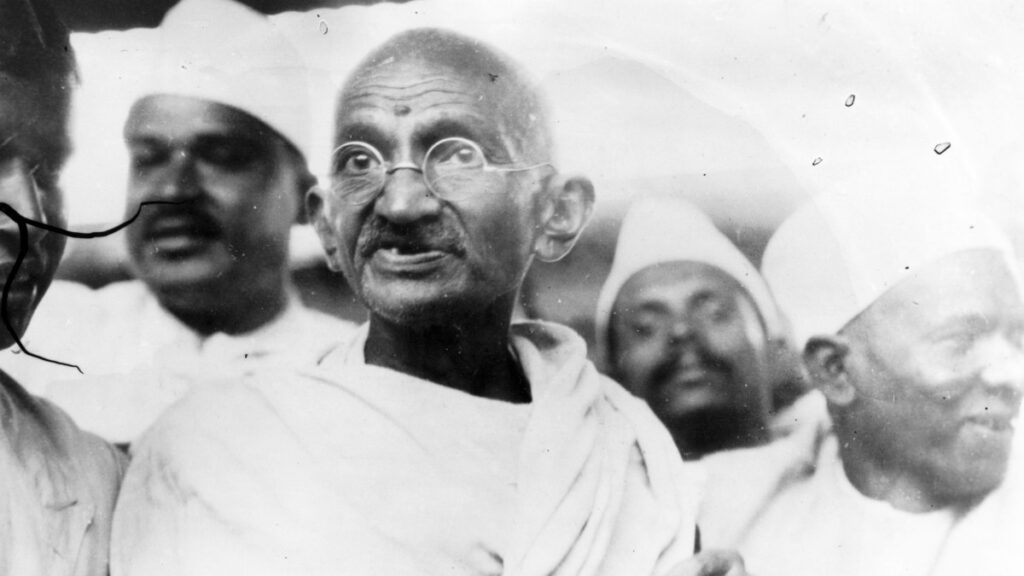

Former US President Barack Obama has said that his fascination with India largely revolved around Mahatma Gandhi, whose “successful non-violent campaign against the British rule became a beacon for other dispossessed, marginalised groups”.

However, the 44th US president, in his latest book, rues that the Indian icon was unable to successfully address the caste system or prevent the partition of the county based on religion.

In his book “A Promised Land”, Obama writes on his journey from the 2008 election campaign to the end of his first term with the daring Abbottabad (Pakistan) raid that killed al-Qaeda chief Osama bin Laden.

“A Promised Land” is the first of two planned volumes. The first part hit bookstores globally on Tuesday.

“More than anything, though, my fascination with India had to do with Mahatma Gandhi. Along with (Abraham) Lincoln, (Martin Luther) King, and (Nelson) Mandela, Gandhi had profoundly influenced my thinking,” writes Obama, who had visited India twice as president.

“As a young man, I’d studied his writings and found him giving voice to some of my deepest instincts,” the former US president said.

“His notion of ”satyagraha”, or devotion to truth, and the power of non-violent resistance to stir the conscience; his insistence on our common humanity and the essential oneness of all religions; and his belief in every society’s obligation, through its political, economic, and social arrangements, to recognise the equal worth and dignity of all people — each of these ideas resonated with me. Gandhi’s actions had stirred me even more than his words; he’d put his beliefs to the test by risking his life, going to prison, and throwing himself fully into the struggles of his people,” Obama writes.

Gandhi’s non-violent campaign for Indian independence from Britain, which began in 1915 and continued for more than 30 years, hadn’t just helped overcome an empire and liberate much of the subcontinent, it had set off a moral charge that pulsed around the globe, he writes.

“It became a beacon for other dispossessed, marginalised groups – including Black Americans in the Jim Crow South – intent on securing their freedom,” says Obama.

Recollecting his first visit to India in November 2010, Obama said he and then First Lady, Michelle, had visited Mani Bhavan, the modest two-story building tucked into a quiet Mumbai neighbourhood that had been Gandhi’s home for many years.

“Before the start of our tour, our guide, a gracious woman in a blue sari, showed us the guestbook Dr King had signed in 1959, when he’d travelled to India to draw international attention to the struggle for racial justice in the United States and pay homage to the man whose teachings had inspired him,” he writes.

“The guide then invited us upstairs to see Gandhi’s private quarters. Taking off our shoes, we entered a simple room with a floor of smooth, patterned tile, its terrace doors open to admit a slight breeze and a pale, hazy light,” he said.

“I stared at the spartan floor bed and pillow, the collection of spinning wheels, the old-fashioned phone and low wooden writing desk, trying to imagine Gandhi present in the room, a slight, brown-skinned man in a plain cotton dhoti, his legs folded under him, composing a letter to the British viceroy or charting the next phase of the Salt March,” he said.

“And in that moment, I had the strongest wish to sit beside him and talk. To ask him where he’d found the strength and imagination to do so much with so very little. To ask how he’d recovered from disappointment,” he wrote.

Obama said Gandhi had had more than his share of struggle.

“For all his extraordinary gifts, Gandhi hadn’t been able to heal the subcontinent’s deep religious schisms or prevent its partitioning into a predominantly Hindu India and an overwhelmingly Muslim Pakistan, a seismic event in which untold numbers died in sectarian violence and millions of families were forced to pack up what they could carry and migrate across newly established borders,” he said.

“Despite his labours, he hadn’t undone India’s stifling caste system. Somehow, though, he’d marched, fasted, and preached well into his seventies – until that final day in 1948, when on his way to prayer, he was shot at point-blank range by a young Hindu extremist who viewed his ecumenism as a betrayal of the faith,” Obama writes.