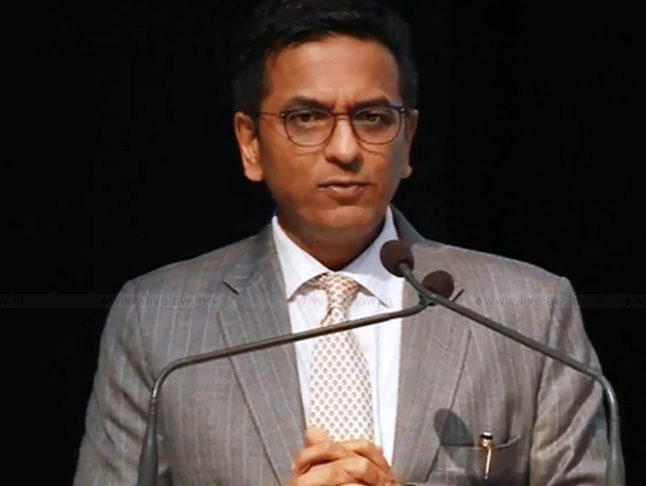

Caste no bar, class no bar, art no bar: Justice Chandrachud on why freedom and art are soulmates

Aug 23, 2019 | PRATIRODH BUREAUJustice D.Y. Chandrachud at a recent event spoke about Dalit Panthers, Toni Morrison, Banksy and how art has provided liberation to the oppressed.

In his keynote address at the 20th D.P. Kohli Memorial Lecture in memory of the first director of the agency, the CJI said that in the realm of criminal justice, the delicate balance between search and seizure powers of agencies like the CBI and individual privacy rights stands at the cornerstone of a fair and just society

Art communicates that which is socio-political, just as it entertains. You know the eyesight of judges and lawyers can be myopic – the results of long hours in book-line chambers, which does not allow the sunlight to filter in contributes to this myopia. But by harnessing the power of imagination, art allows us to see the unseen and hear the unspoken.

As Berys Gaut said in a beautiful book in 2007 called Art, Emotions and Ethics, “by deploying the full force of effective and experiential imagination, we can be made to feel the rightness, wrongness and sheer imponderability of certain moral choices and so we can learn through imagination”.

In this presentation this evening, I take you on a journey where freedom and art are soulmates.

Art fosters social debates

Art it is often said, is a bastion of true freedom. Cultural freedom is the heart of political freedom. Art is a pursuit through which the artist kindles a sense of the possible. For centuries, art has been used to visualise a better world – to believe that the shackled can shed shackles, so that human beings can open their hearts and minds to each other. The libertarian idea of constitutional law wants all individuals to be autonomous and rational. But as a judge, I have found that rationality does not make us immune from intellectual materialism. We cling to our intellectual positions in the face of contrary opinion that challenges our world view. By foregoing the purely intellectual and appealing to our collective consciousness – intellectual, emotional and physical – art sets alight ideas within us which we might otherwise dismiss for the fear of being wrong.

Engaging audiences more effectively that academic or political discourse, art fosters a vibrant social debate. It gives birth to spaces for counter-discourse that subvert existing centres of power and authority. For example, irrespective of whether street art leaves its mark on public or private property – I used to be fascinated by this sign in Mumbai when I was growing up called ‘stick no bills’. I thought it was the name of a building. Whether it is right or wrong, it entails a demand that more space be shared.

Street art involves a struggle against the culture of the powerful and brings to the fore questions of accessibility to public spaces. Artists from across the globe descended on Lodhi Colony in New Delhi to decorate stark government buildings with incredibly vibrant paintings. Graffiti to some, this recapturing of public spaces using street art symbolises liberation. As an artist said, “transgenders who are compelled to beg for alms on the street, now find themselves immortalised on the walls of these very streets”.

Graffiti to some, this recapturing of public spaces using street art symbolises liberation

The British street artist, Banksy, used stencils for graffiti because it allowed him to paint faster before the police arrived. He later recounted and said, “As soon as I cut my first stencil, I could feel the power there. I also like the political edge. All graffiti is low-level dissent, but stencils have an extra history. They have been used to start revolutions and stop wars.”

He was proven right when a group of teens in Daraa painted anti-government slogans on the walls of a school, kickstarting the Syrian chapter in the Arab springs. The protestors and rebels continued to fight day after day. Artists continued to create a new imagery to encourage them to redeem their pledge of freedom.

During the Bengal famine of 1943, Chittaprosad Bhattacharya trudged on foot from village to village with a notepad and ink pen and brush in hand. His illustrations captured a record of what it meant to be poor during a famine. In his sketches, Chittaprosad highlighted the role of colonial rule and global capitalism in creating a deadly food crisis. Art portrayed the inhuman face of a colonial government in Westminster, which placed the success of the great war over the lives of the starving. Each sketch of his series, Hungry Bengal, acknowledges the hard reality of villagers. One of his sketches, portrays a group of women taking shelter under a tree and staring into the distance – glassy-eyed and clinging on to their hungry children. Dacoits had stolen their half-boiled rice leaving them and their children to starve. Such was the stark power of Chittaprosad’s art that a British administration, confiscated and destroyed almost all copies of Hungry Bengal. We in fact have a provision in the CrPC Section 95, which legitimises the destruction of literary pieces. The 2019 movie titled The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind recounts a similar tale from Malawi where riots broke out because of government rations and dacoits robbed families of their last morsels of food. So, Bengal or Malawi, art reminds us of the universality of human experience.

All art is political

In social movements throughout history, the sheer act of depiction has laid bare the forces of violence, of oppression, of injustice, of inequality by addressing socio-political issues and challenging the hierarchies imposed by those in power – the restraints, the traditions, the limits by those in power.

Art opens the space for the marginalised to be seen and heard. Let’s not forget, all art is political. If it were not, art would merely be an ornament – of colour, of words, or music. It is this power of art that I wish to share with you today. The power of art to imagine and re-imagine what it means to be free in the realities that we face.

Let’s not forget, all art is political

Is freedom all about protecting our liberties against the state? A judge’s task is associated with the ideal of protecting personal freedom against excesses of state power. But this to my mind is a reductionist view of law and life. Amartya Sen reminds us that our success as a society, should not be measured only by how well we restrict government overreach or by our per capita GDP. Bhutan gives us a definition of gross domestic happiness. Sen argues that we must evaluate if we give our citizens the substantive freedom to lead the lives they want and the circumstances they face.

Neither freedom’s simpliciter nor money can by themselves overcome the discrimination, stigmatisation, marginalisation faced by our society. Dr Ambedkar presciently stated that if liberty means the destruction of the dominion which one man holds over another, then obviously it cannot be insisted that economic reform be the one kind of reform worthy of pursuit. If freedom is the measure of our ability to pursue the life we want in the circumstances that we face, it is possible that our freedom is curtailed not only by the government but by the societal realities of the day. Thus, when we speak about the power of art to imagine freedom, it is not in a limited sense, it is not merely freedom against oppressive government regimes but also the unfreedoms that we as citizens subject each other to every day of our lives. Thomas Vernon Reid documents that people have resisted the dominant discourse and expressed their views using a hidden transcript – in the form of jokes, folklore, songs and theatre, faced with societal oppression and conditions of slavery and in concentration camps.

The instrumental power of art brings to the forefront, not the act of doing something, but what the act really signifies. Art with its nuances of creation and creating, of metaphor and embedded meaning, can communicate an expression where words fail. Art as a process, sight and form, enhances the understanding of the human condition through alternative processes and representational forms of enquiry. In that sense, art serves both an intrinsic purpose – to allow the exploration and shaping of identity leading towards a self-actualisation of human beings as well as an extrinsic purpose of bringing into collective consciousness the vast unfreedoms and oppressions that plague our society.

Art to fight caste

Today, I wish to focus on the relationship of art with three distinct areas: Firstly, caste. Second, disability. And third, the environment.

The first, the artist presents a narrative about their subjects, which can shape and re-shape identities. Narratives are of relevance to communities who have historically been subjected to systemic oppression. In extreme cases, if such communities allow the dominant discourse to dictate their narrative, they risk the very obliteration of their identities.

An excellent example of resisting the obliteration of identity is Dalit literature, which operates as a counter-discourse, not just against the oppression faced by the community, resulting in systemic discrimination and abject poverty, but also resists the co-opting of the community’s narrative by those on the outside. Those on the outside become more of the Dalits and greater than the Dalits themselves. That is the seizing of the narrative of the Dalits by the outside community.

Members of the Dalit community have often struggled against negative identities – of impurity and inferiority. However, with the emergence of Dalit literature, the histories and lived experiences of the marginalised have gained representation. The flourishing of Dalit literature sees the attachment of a new connotation to the word ‘Dalit’. The term Dalit, in other words, came to be identified in other words as those whose culture had been deliberately broken, crushed to pieces or ground down. The adoption of the term signified an affirmation of the Dalit community’s struggle for cultural independence and a re-assertion of their distinct positive personality.

The process of imagining a Dalit cultural identity involves a move beyond the connotation of pain and suffering associated with the traditional untouchable identity and towards an exploration of a positive characteristics of Dalit identity. This involves a complex process of re-naming, ascribing old objects or even cultural practices with new meaning. For instance, the Hindi Dalit writer, Surajpal Chauhan, in his autobiography Tiraskrit, attempts to break stereotypes of impurity associated with caste. He writes about the festive atmosphere accompanying a wedding feast in the mohalla, depicting the process of catching a pig as a game with a cheering crowd. For those of you who have read the English recent book by Sujatha Gidla, Ants Among the Elephants, she speaks about a similar occurrence. Eager children gather around to watch the cutting of the meat and devour pieces of the pigskin. In his descriptions, Chauhan emphasises a skill necessary to catch a pig, an expertise needed to carve the meat without puncturing the organs. By doing this, the author manages to subvert the gaze of impurity through which a Dalit practice is viewed. He reinterprets an event which is regarded with disgust among non-Dalit sections of society as an event involving skill and celebration.

Through their writings, Dalit autobiographers attempt to recapture old meanings and give positive meaning to their community’s social traditions. Dalit writers assert that Dalit society has its own unique traditions and customs, full of joy and inventiveness. And forming part of the mosaic that our culture embodies. Dalit literary movements are imbued with political meaning and intent. Writers and poets were the founders of the Dalit Panthers. In the 1960s, literary expression was used as a medium to further a political message, to create caste consciousness and disseminate the message of emancipation from caste discrimination.

Dalit autobiographers attempt to recapture old meanings and give positive meaning to their community’s social traditions

The Panthers’ writings questioned the political and social order and challenged the literary monopoly of dominant caste groups. They created a new language through which Dalit resistance to oppression could become a part of public discourse. This empowered a Dalit to become a poet and then an activist. Political purpose, social emancipation and literature are inextricably linked together.

Interestingly, the manifesto of the Dalit Panthers claims a close affinity with the struggle for racial equality in America, offering an analogy between racism and casteism. Understanding the relationship between the literary movements of Dalits and African-Americans requires not only tracing the historical influence literature had on writers, but also sheds light on Dalit literature as a counter-discourse of oppression. By capturing the complex relationship between the individual protagonist and the larger community, both Dalits and African Americans have used literature as a means of making a broader political statement about their marginalised positions in society. Individuals from a community who present a personal account of their experiences provide an opportunity for society at large to gain an understanding of the community’s quest for equitable existence.

A writer who recently left us but whose writings have left an indelible impact not just on the literary world but humanity is Nobel Laureate Toni Morrison. In a collection of essays titled The Origin of Others, she wrote, “The resources available to us for benign access to each other for vaulting the mere blue air that separates us are few but powerful – language, image and experience.”

Through her literary work, which could be described as an exploration of the Black identity, Morrison highlighted the myriad ways in which the fallacy of racial inferiority pervaded the private lives of African Americans. In her work titled the Bluest Eye, Morrison narrates the story of a little African girl who yearns obsessively to have blue eyes. A standard of beauty imposed on American women. Morrison emphasised that she wrote for Black women – a community she belonged to, to narrate their lived experiences and to communicate to readers a rare insight into a world from which they were too often far removed. Artists have used unconventional methods to depict oppression and challenge the hegemonic structures of society. The Casteless Collective is a band which has been set up by renowned Tamil director, Pa. Ranjith, which brings together hip-hop, rap artists and singers from the Dalit community. The songs reflect the group’s defiance of caste, which dictates that if you belong to the lower caste you don’t get to have a voice and express a narrative.

Use of new forms of art widens the reach of the message. New forms bring the young into the fold, of being art-lovers. In January last year, The Casteless Collective performed in Chennai, dressed in grey suits like Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar, with a giant image of him projected in the backdrop to an audience of 4,000.

I’m sure we have our favourite tongue-in-cheek Amul ad. On the eve of the historic Mandal Commission report, recommending reservations for OBCs, Amul ran the line: Caste no bar, class no bar, Amul bar-bar. That is an artistic amalgamation of the commercial and the political.

Art has provided liberation to oppressed communities by providing an outlet to express pain and suffering. In that sense, it serves as a medium to express unfreedom. The Bangalore-based ‘Aravani Project’ is providing the transgender community a platform to narrate their lived experiences. It comprises of a collective of women artists who identify across the spectrum as transgender women, gender fluid women and cis-gender women. We in fact spoke about the fluidity of our sexual experiences when we were evolving some legal doctrine in the judgment on 377. This is a collaborative public wall-art project aimed at raising awareness in public spaces and gently re-shaping the politics of inclusion and exclusion that surround gender-identities. Through murals and street art, the focus of the project is on sharing stories. While some of the stories narrated through the art of this group are hopeful, some can be described only as devastating. For instance, a 60-feet high mural in Chennai, was created in memory of Tara, a 28-year-old trans woman who suffered 90 per cent burns and died barely six months before the collective went to Chennai. Tara worked as a sex-worker.

Art has provided liberation to oppressed communities by providing an outlet to express pain and suffering

You would be surprised almost 80 per cent of the cases that we deal with as judges, deal with this kind of debilitating insult and injury and crime against women.

Tara worked, as I said, as a sex worker. The mural featuring Tara is called ManidhamMaralattum, which may be translated from Tamil as: let humanity bloom. By giving recognition to the sufferings of a community, art can also heal. There is a term called ‘beeli’, that’s prevalent in the trans community which translates to giving back or fighting back. The expression of art grants validation to the lived expression of oppressed communities and serves as the community’s beeli.

Art to understand disability

I have dealt at some length of the power of art to overcome oppression, arising from the societal realities of caste and power and gender. Art itself is often an expression of a yearning for freedom.

For the disabled, art may be the only method of communicating their experiences of freedom. Judith and Joyce Scott were born as twins in 1943. Judith was born with Down syndrome and was also hearing impaired. At age 7, the sisters were separated. Judith was sent to a state institution after being classified as ‘uneducable’. She was released after 35 years when Joyce became her legal guardian. Judith would go onto become a world-famous and world-renowned artist, creating intricately woven sculptures by wrapping fibre around everyday objects – a toothbrush, a bottle. Later, Joyce was to recount, “The first piece of Judy’s work I saw were two humanoid figures wrapped in fibre with tender care and in that moment, I knew that she knew that we were twins together, two bodies joined as one.”

The power of visual art stems from its ability to transcend the constraints of the spoken and the written. The tale of Judith and Joyce reminds us of the power of visual art. Allowing a physically challenged person to whom neither the spoken nor written communication was possible, to communicate their own freedom. To look at the work of Judith Scott through the lens of her disability alone is itself, I would argue, a disservice. Thinking about the disabled doing art, is to focus on the difference between the disabled and the non-disabled. It creates a culture where disabled artists are admired for being able to create works of art at par with the non-disabled. However, by harnessing the power of art to stimulate self-reflection, disability artists create art which critically engages our social construct of disability itself. Works of art that engage explicitly with the disabled body serve to critique our assumptions of idealistic aesthetics.

The power of visual art stems from its ability to transcend the constraints of the spoken and the written

In 2007, the Tamil director Radha Mohan created a romantic comedy, Mozhi, featuring a hearing-impaired movie. After the film, Mohan commented, “Physically challenged actors have always been portrayed in Indian cinema and theatre as serious, sad human beings with no sense of humour. They are always tear-jerkers and scream sympathy. But I wanted to portray Archana, the heroine, as a confident, positive person who doesn’t need anyone’s sympathy.” Performances such as this illuminate and subvert our discriminatory attitude, which looks at the disabled as objects of charity. They lay the foundations for disability to grow its own positive, social identity. Where the disabled are not looked at as the other. As [Allan]Sutherland notes in a seminal piece on the subject, “Our politics teaches us that we are oppressed not inferior.”

One of the most striking examples of disability art is the work of Carrie Sandahl. Sandahl walks among the audience in a white lab coat and white pants. On the white clothes she wears through the course of her performance are printed the comments and questions that she has experienced in everyday life and the questions she faces as a disability artist are – Are you contagious? Were you born like this? Do you ever dream that you are normal? Can you have children? In fact, when we were hearing the challenge to our earlier verdict, that’s not on the question of disability of course, but on the LGBTQ rights. One of the lawyers mentioned that in the earlier rounds in the Supreme Court, one of the questions that came from the bench was – have you ever met somebody who is homosexual? We had to right a wrong after several decades.

Disability art, at its best, seeks to repurpose the emotions of shame or the notion that disabled persons need to be fixed, to advance the idea that disability is a natural part of the human experience. Such art forces us to critically evaluate how we, as the disabled or the non-disabled, contribute to the stigmatisation and marginalisation of our fellow citizens. The law undoubtedly plays a role in the process, but as I increasingly realise with my work in the law, the court can only police the existing boundaries of the law. If we can use the arts as a laboratory for a more inclusive society, we can be ahead of the law and model new ways of being together and creating a better world.

Art to fight environmental degradation

When we speak of new ways of living together, art reminds us that we live together on this planet not just as humans, but as broader interconnected web of organisms. The unavoidable entwining of human actions and nature has far-reaching consequences for our future. Artists can combine art and environmental degradation into shades of artistic expression. Do artists see themselves as communicators of the doomsday predictions espoused by climate scientists or do they draw on the experiences of environmental degradation? No matter what the source of their inspiration is, it is interesting to see how ecological art has allowed us to reflect upon and shape our environmental understanding, while contributing to the emergence of an ecological consciousness. Contemporary and non-contemporary forms of ecological art have an important role in shaping and defining who we are and what kinds of choices we are going to make to create a sustainable planet.

Contemporary and non-contemporary forms of ecological art have an important role in shaping and defining who we are

Ecological themes portraying environmental destruction as well as creative alternatives that explore environmentally sustainable modes of life are widely displayed in the form of paintings –in galleries, street art, comics and even mobile apps. We are often desensitised to information about environmental degradation from sources such as the news. Creative expressions of climate change do not seek to impart information, but cause us to feel at a primal level, the dangers associated with climate change.

The Pixar production of the animated movie Wall-E is a cinematic poem of wit and beauty with a sombre reflection of our potential extinction from ecological damage. The ecological parable directed by Andrew Stanton is based in a dystopian future and is centred around an industrious robot janitor and his loyal cockroach sidekick. They live in a city engulfed by a post-apocalyptic silence and covered by piles of garbage bereft of any human or animal inhabitants. The director has used his story-writing and direction skills to transform his sense of environmental consciousness, to highlight the dangers of overconsumption and environmental destruction through the medium of popular cinema. Such artistic expression can inspire audiences, including children, at a profound level and remind us of the ongoing threat of environmental change.

A person by the name of Biboy Royong of the Philippines literally created art out of rubbish. He was inspired by real whales that had died and washed up on shore with pounds of plastic debris in their bellies. To raise awareness of ocean pollution and the pressing need to preserve the aquatic habitat, the artist unveiled on Earth Day this year, ‘The Cry of the Dead Whale,’ a 78-feet outdoor whale installation made out of plastic bags, bottles and straws dispersed on the shoreline. In Korea, Greenpeace installed a sculpture of a mother holding a daughter’s hand. The daughter is made out of ice. The sculpture carries the description – Global warming: our future is disappearing. Tourists and onlookers witnessed how in a matter of few hours, the daughter had melted away. It allowed viewers to emotionally connect with the problem of increasing Earth temperatures and its impact on our coming generations.

These examples outline how imagination can play a key role in stimulating collective consciousness and in creating the critical mass necessary for effective and meaningful change in societies. Unlike the alarming figures of increasing CO2 levels in our atmosphere that flash on our TVs and smartphones, on a daily basis, artistic expression allows viewers to emotionally connect with our existing and future realities and facilitate a more holistic understanding and response to collection active problems such as climate change.

A New York-based animation artist by the name of Jeff Hong has portrayed Disney’s most popular characters as battling the grim conditions faced by many communities across the world. In one image, he depicts the most famous mermaid, Ariel, emerging from a filthy sea, her fins slick with spilt oil and stuck with plastic waste. In another image, he has displayed a famous Disney character Mulan, being forced to cover her face while walking around the smoggy streets of contemporary China. The artist through these images has tried to make a bold sociological statement and stresses that if we do not safeguard the planet, our fairytale will certainly not have a happy ending.

Freedom to resist

I hope that the issues I have discussed today have brought to the forefront the power of art to imagine what truly means to be free and perhaps more importantly, to continually critique our current existence, creating an ever-expanding horizon of freedom.

Freedom is not just for us here today but for all generations to come. Before I conclude, a few cautionary points. We must remember that the freedom of future generations is premised on them having a habitable world to live in. The freedom for art to expand in all directions is necessary for humanity’s collective progress. The danger lies when freedom is suppressed, whether by the state, by the people or even by art itself. Ironically, a globally networked society has rendered us intolerant of those who do not conform. Freedom has become an avenue to spew venom on those who think, speak, eat, dress and believe differently.

The threat to restricting art may arise within art itself as a result of the dominance of privileged groups over the domain of art and literature. The lived experiences of oppressed communities are often excluded from mainstream art. Thus, pushing the identity of the community into relative obscurity. By denying certain communities a voice and a narrative, art can itself be oppressive and enabling of a hegemonic culture. Through his subaltern work, Magsaysay award-winning Carnatic musician, T.M. Krishna is participating in another kind of struggle – the struggle to include. Recently, he conducted a concert titled ‘Performing the Periphery’ with Jogappas, a transgender community who identify themselves as people who have been touched or possessed by the goddess Yellamma. Interestingly, Krishna described the concert as a conversation of multiple sexualities and multiple cultures through multiple music. By performing with the Jogappas, Krishna shattered multiple barriers associated with the artform and allowed for inclusion in the field of classical music, which has often been the privilege of the most privileged of our communities in the caste structure.

We see that where art itself perpetuates a cultural hegemony, there are attempts by artists to resist this oppression and give voices to the narratives of the most marginalised. Far more disturbing to my mind is the suppression of art by the state.

The behemoth of the State necessarily moves incrementally. However, art moves in leaps and bounds, often in no particular direction – whether it be the Bandit Queen or whether it be Me Nathuram Godse Boltoy or whether it be Padmaavat or whether it be, just two months back, Bhobishyoter Bhoot, which was banned by the West Bengal government because it was a spoof on ghosts among politicians. The politicians were deeply disturbed by the fact that here was this director who actually had the audacity to talk about the ghosts amongst politics. Have we changed? However, the very nature of art is that it moves in leaps and bounds, as I said, often in no particular direction.

Art which challenges the status quo may necessarily appear radical from the viewpoint of the State, but that is not a reason to suppress art

Art which challenges the status quo may necessarily appear radical from the viewpoint of the State, but that is not a reason to suppress art. The threat is real, as the UN special rapporteur in the field of cultural rights Farida Shahid has noted, “Artistic expressions and creations come under particular attack because they can convey specific messages and articulate symbolic values in a powerful way. Motivations for restrictions stem from religious, political, cultural, moral or economic interests and disturbing cases of violation are found on continents. Often, removing creative expression from public access is a way to adopt, to restrict artistic freedom by oppressive regimes across the world.”

Finally, we must not forget that there is a democratic, egalitarian commitment in an act of imagination. The freedom of artistic expression and creativity cannot be disassociated with the right of all persons to enjoy art. Restrictions in artistic freedom aimed at denying people access to specific artworks should always be viewed with the gravest suspicion.

Independence and art

In conclusion then, I was having a chat with Zia [Modi] yesterday and I was asked whether art was an unusual choice for an Independence Day lecture. And let me now give a brief reason as to why I chose this. The most immediate goal of our freedom was political freedom from colonial rule. However, alongside this movement for political change and a transfer of political power, there existed a parallel movement for social freedom and for emancipation to end the oppression for Indians by Indians. A movement which often found expression in art. Independence was not just a witness to a transfer of political power from a colonial regime, it was and continues to be an aspiration for transformative change. Independence was meant to mark a fundamental shift from a culture of authority and power to a culture of justification and rights.

Art is a symbol of that shift and has limitless preserve to bring about this transformation. Through the act of depiction, art can breathe life into the world of ideas where we exist without oppression. We increasingly witness today a world of intolerance where art is suppressed, defaced and co-opted. Attacks on art are attacks on freedom itself. You all know what has happened to M.F. Husain.

Art can breathe life into the world of ideas where we exist without oppression

In adopting the Constitution, the founding generation of our nation penned down the freedom to express ourselves. To ensure that this freedom does not remain but a dead letter of the law, we must live and fight for this freedom every day of our lives.

Art grants a voice and a narrative to oppressed communities, resisting majoritarian hegemony. Art invites us to explore the darkest crevices of our minds, instigating self-reflection on how we as individuals can make our society a better and kinder place. This is a value to be cherished and protected. We celebrate our Independence Day because on the 15th of August 1947, we broke free from the shackles of colonial rule and began to chart our own path as a nation. But our independence is as much a celebration of the freedom we achieved on that day in 1947 as it is an aspiration of the freedom that is yet to come. Art can be understood as a thread weaving together our past, present and future. While a piece of art may be created in a single moment, it is simultaneously timeless, offering us a lens through which to look at the past, challenge the present and portend the future.

Art may be fixed as in the case of a poem or it may be ephemeral as in the case of a sand sculpture, which is washed away by the evening tide. We must believe in the permanence of the artist’s message in the same vein in which we confront the transient nature of the artist’s existence.

Toni Morrison had this to say in her Nobel acceptance speech: “We die. That may be the meaning of life. But we do language. That is the measure of our lives.” Therefore, I really conclude by saying that art is the gadfly, which provokes, but art is also the liniment, which yields our quest for freedom, reflects the continuous and continuing yearning, a wick within our souls which illuminates our desire to be free, as a daily reminder of how tenuous freedom can be and even of its impermanence, art brings sustenance to that quest. The message of freedom that art embodies is in that sense, everlasting.

This is an edited excerpt of Justice D.Y. Chandrachud’s speech on 17 August 2019 at the Independence Day lecture organised by JSW Group at the Oberoi Trident, Mumbai.