Book Review: A Frank, Fearless Autobiography Of India’s Snakeman

Feb 17, 2024 | Pratirodh Bureau

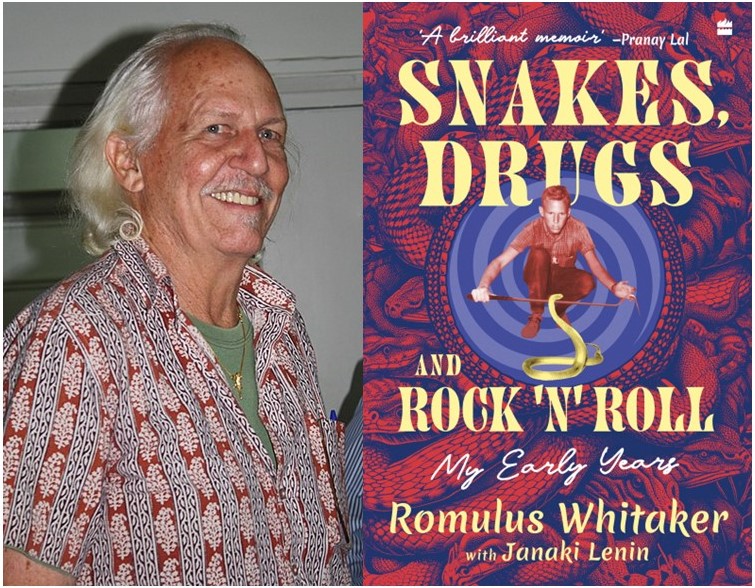

(Left) Romulus Whitaker at an event in Mumbai in 2013. Photo by Dr. Raju Kasambe/Wikimedia Commons. (Right) An image of his early days with snakes on the cover of his new memoir (Photo from Harper Collins India)

- Unconventional and adventurous, herpetologist Romulus Whitaker’s new book ‘Snakes, Drugs and Rock ‘N’ Roll: My Early Years’ is a candid reflection of his journey to becoming one of the most famous Indian conservationists.

- From exploring his upbringing in the U.S., and his discovery of being allergic to snake venom, to forming an aversion to too much discipline, Whitaker’s story contains grit, hilarity and does not shy away from the uncomfortable aspects of his past.

- His enduring passion for snakes dominates the autobiography, which also explains the origins of his determination to build a snake park and dedicate his life to dispel myths about snakes and other reptiles.

A delightfully unapologetic, racy and often hairy coming-of-age story, Snakes, Drugs and Rock ‘N’ Roll: My Early Years is an engaging account of ‘Snakeman’ Romulus Whitaker’s life and his abiding passion for snakes, nature and solitude. At the outset, he declares that he is not a conservationist and it is a label that others have foisted on him. Yet he can boast of a string of awards for his work in conserving habitats, protesting against the Silent Valley Project by writing articles, founding various NGOs including the Madras Crocodile Bank and Snake Park, working with the Irula community, as well as the Agumbe Rainforest Research Station in 2005, authoring papers, and books, producing a stunning TV series featuring king cobras and so on.

This book is ostensibly an account that shows him with ‘all his warts’, in his own words, and makes him more of an anti-hero, though his escapades are unequivocally heroic. Even if he shirks off the label of conservationist, his work on snakes has largely transformed the stereotypical perceptions surrounding them and the dread of snake bites.

Whitaker’s vision was much larger than saving a particular species and often encompassed protecting entire habitats. Despite some unconventional ideas about saving some species, for which he has been criticised in the past, he is not entirely a non-conservationist.

The first volume of Whitaker’s autobiography is as breezy as his nickname. The table of contents offers a glimpse of what is in store. For example, ‘Year of fishing’, ‘Year of Stuffing Birds’, ‘A Year of Vices’, one for explosives and later on in section 2, ‘Snakeman’ and ‘Commercial Hunter’, give an idea of Whitaker’s many adventures. It describes the early years of his life, his education in Kodaikanal, his aversion to any form of regimentation, his unsuccessful attempts to cope with studies, his increasing love for solitude, wildlife, fishing and camping in the wild, qualities he adapted well in the US, where he enrolled for higher education.

By the time Whitaker returned to India at 24, he had already lived a few lifetimes with a brief and unhappy university education in the US, working as a salesman, a seaman and later, as a lab technician in the US Army where, as he writes, he was thankfully not drafted to fight against Vietnam. He occasionally went jacklighting and has shot animals (luckily missing a leopard once in India), caught masses of snakes, other reptiles and amphibians either for venom or for trade while he lived in the country of his birth for seven years. His passage back to India from the US was paid for by a collection of 500 rattlesnakes, a breathtaking climax to the book.

As always, he humanises snakes and the episodes about catching them, even if not always happily, and his tenure with Bill Haast, his hero and the founder of the Miami Serpentarium, form the most fascinating parts of the book. His stint with Haast sowed the seeds of an idea that he would eventually turn into reality in the form of the Madras Snake Park (currently Chennai Snake Park) and the public display of extracting snake venom by the Irulas, which became a major attraction.

In the mid-1960s, there were only a few wildlife protection laws in place in countries, including the US, and snakes were transported freely all over the country and abroad. The 35 rattle snake species in the US, featured in stunning photographs in the book, are not only strikingly beautiful but huge, making them deceptively appealing as they sun themselves or spread out over rocks.

The autobiography also gives glimpses into the rich natural history of the United States of America, but also its easy access to guns, which delighted a young Whitaker used to a stricter regime in India as a schoolboy. Lurking at the back of many episodes of snake and lizard or even frog and the occasional alligator-catching is the underlying uneasiness of how this would impact wildlife, and also a forewarning of the invasive species that would infest many parts of the country, like Florida.

Whitaker has a matter-of-fact approach to the discovery that he had colour blindness, and, curiously, an allergy to snake venom. After being bitten by a prairie rattler, he stops for a coffee to decide what is to be done before walking into the hospital with a swollen hand. At that moment, he realised he is allergic to venom and that cryotherapy did not work for bites. He spent his recovery reading Carl Kauffeld’s book on snake hunting several times and even writing to him. He remains calm after snake bites despite the dangers and pain, and debates the next moves, at times delaying anti-venom injections, the remote location being one reason. Once, on a hunting trip, his friend Attila, after being bitten by a timber rattler, says, “Let’s sit and think and think about what to do”. Luckily, it was a dry bite. These experiences may have something to do with Whitaker becoming a firm advocate of not panicking after a snake bite and seeking immediate medical attention.

The book offers a glimpse of his affectionate family, including his siblings, and, in particular, his mother Doris, who gave him his first book on snakes and tried to dissuade him, unsuccessfully, from killing animals. His father was a murky figure who later remarried and Whitaker was much closer to his stepfather Rama, the son of Harindranath and Kamala Devi Chattopadhyay. Both grandparents are objects of fond reminiscences. His life in then Bombay, which seemed as crowded and busy as ever in the 1950s and 1960s, and those of his school life in the Kodaikanal hills, could not offer a greater contrast.

The autobiography hasn’t ‘airbrushed‘ his bloodthirsty past, as he writes. Whitaker was not immune to the ‘coming-of-age’ hunting and bloodletting of those days. However, growing up in 1960s America as a teenager, unable to sport long hair as he was in the US army, he was very much influenced by the music of his times: Bob Dylan, Barry McGuire and Tom Paxton, among others, and the anti-war sentiment that prevailed. His explorations into the use of drugs including peyote, the potent cactus which contains mescaline, a hallucinogen, and other drugs are candidly described.

A hilarious anecdote is of Whitaker giving a rather preachy Baptist missionary, his companion on the ship voyage to India, a book on peyote, which shuts him up. The book has other light moments and one liners, and the funniest episode is about an anaconda wrapping itself around Whitaker, who was extricating it from a shipment, much to the amusement of his companions who did nothing to help!

While other boys may have photos with their first toy car, Whitaker has one with his first snake in 1947, his pet python at school in Kodaikanal, and Shangrila the kite in Bombay. He has an abiding love for motorbikes as well and often scrounged out money for a Norton, a Triumph, BSA or an AJS. On his 24th birthday, Whitaker spent the day hiking with friends and catching a Mojave rattler, which was his first ‘tiger’ rattlesnake and a few more which capped the hunt for 500 snakes which would pay his passage to India. A few days before that, he was bitten by a green rock rattlesnake. Even though it caused a brief bout of blindness, some pain and swelling, it didn’t stop his snake hunt. His desire to travel to India overshadowed everything at that point.

In parts, the book is also a memoir of an excited schoolboy in many ways, who hunted birds, learnt to identify and stuff them, and eventually trained in taxidermy under expert hands in Mysore before going off to hunt wild game, and fishing which became an abiding passion. The narrative transports us back in time to a life not governed by mobile phones and computer games where nature and related activities were a compelling attraction. Recreation and adventure had a different flavour and Whitaker’s many escapades as a young boy were probably not uncommon in those days in a Durrellian sense, though few would persist with their love for nature and animals with any seriousness and commitment to form a lasting bond. This volume is a precious account that opens a window into the formative years of a non-conformist naturalist and offers inspiration to current and future generations who would be hard-pressed to leave the comforts of virtual reality for the most part.

(Published under Creative Commons from Mongabay-India. Read the original article here)