Architects Use Comics And Humour To Rethink Sustainable Cities

Nov 7, 2025 | Pratirodh Bureau

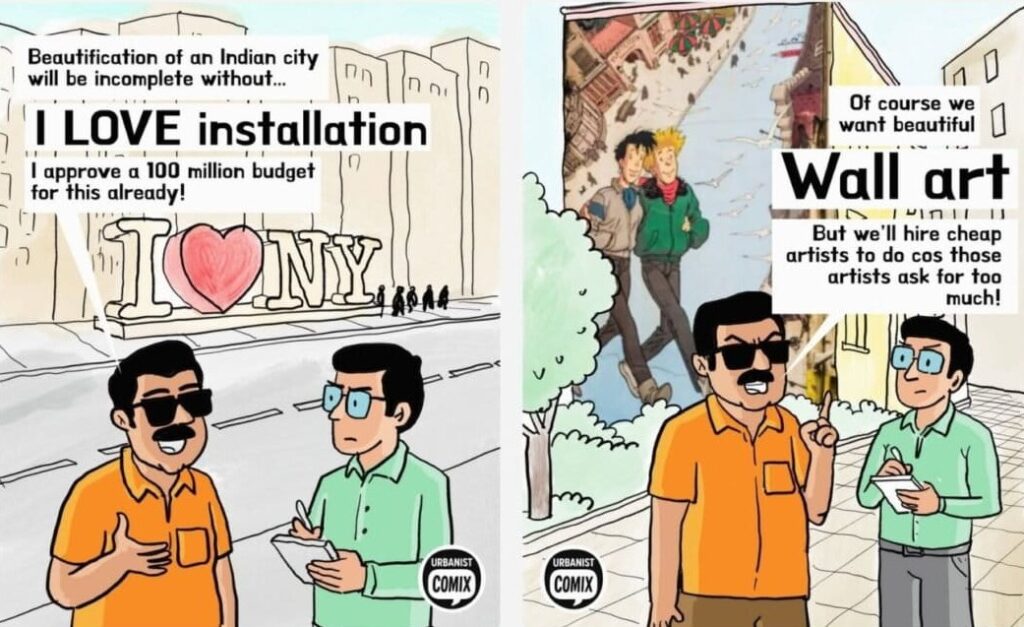

Anuj and Shreya use satire to highlight the misplaced priorities of politicians and the inefficiencies in urban planning decisions (Comic by Leewardists)

- Architects Anuj Kale and Shreya Khandekar use humour and storytelling through Leewardists and Urbanist Comix to make urban issues relatable.

- They suggest that cities should be designed around people and ecosystems — where trees, small open spaces, and everyday informal systems coexist meaningfully.

- Their satirical comics critique car-centric planning and political short-sightedness while sparking conversations on equity, access, and sustainable urban living.

“A city that allows wind to flow, trees to grow, and surfaces to breathe will always perform better than one covered entirely in concrete and glass.”

Wow, if only.

Listening to architects and comic writers Anuj Kale and Shreya Khandekar, the creators of Leewardists and now also Urbanist Comix, made me pause as I looked out of my window. A sea of urban structures, and I have to really look for a bit of vegetation.

Watching Mumbai change almost on a daily basis, I had this question: Why are our cities planned the way they are? I arrived at Shreya and Anuj as I sought answers.

Shreya and Anuj share a deep fascination with cities—how they are formed, how they function, and how they promise a better life to their residents.

“Cities can be thriving ecosystems where self-designed systems be it markets, informal settlements, street economies work beautifully because they are built around people’s real needs.”

Anuj began drawing comics in 2015 while working as an urban designer in Mumbai and started Leewardists, initially a blog featuring comics and writings on architecture. It began as a space to explore the profession—its culture, challenges, and beauty—but the deeper goal was always to return to the city. Shreya helped steer this vision through Urbanist Comix, using stories to capture the everyday joys and struggles of urban life.

Leewardists take inspiration from the term “leeward side of a hill.” A hill has two sides — the windward and the leeward. The windward side faces the prevailing winds and rain, while the leeward side receives less of both.

The leeward side may not appear as lush, dramatic, or beautiful as the windward, yet it’s essential for the hill’s balance and existence. Cities are much the same. They too have two sides — the visible, celebrated one, and the quieter, overlooked one that sustains them.

For Shreya and Anuj, Leewardists represent those who observe and narrate the less-seen side of architecture and cities — the people, systems, and everyday stories that keep them alive.

I really enjoyed the use of satire in your comic strip Politicians as Urban Designers. Could you walk us through how you conceptualised and developed it?

The idea started from real life—politicians often take “study tours” to first-world cities to “learn” from them, but what they bring back are visual elements: wide roads, glass facades, fountains, and cycle lanes without cyclists — almost as if they are window shopping!

We wanted to bring that very absurd but very real phenomenon through satire…what happens when someone with a ton of power but no understanding of urban systems and no faith in people who actually have studied decades to solve these issues—decides to “design” a city?

The humour works because it’s so REAL! In terms of our process, a lot of it usually begins with observation—could be a newspaper headline or an overheard policy statement that makes us think, WHAT!?

We write it till we love it. And then one of us or our very talented team of illustrators who come from different backgrounds – Anik who is an architect and an illustrator, Aditi who is a trained comic artist storyboards, illustrates and we do the final edit. We like to keep cartoons on social media crisp, direct yet layered so that people actually stay, read, think and do something about it.

What does your creative process look like — from identifying an issue to shaping the narrative and final visuals?

Most of our comics begin with observation — something we’ve read, overheard, or mostly experienced in the city. So, when a theme emerges, we spend time researching it like an academic project: reading research papers/policy documents, news, articles and sometimes even interviewing people on the ground. We also do team huddles, ask about their experiences in their respective countries/cities and what is the ground reality for them.

The second stage is writing. We don’t start with visuals; we start with a script, what are we trying to say and why does it matter? Also because we are not trained comic artists we have tried to define a method that works for us. Then comes storyboarding, breaking that intent into very quick sketches on paper or digital and then the final illustrations, colours, editing. We write our comics almost like films, in fact for longer scripts that we are writing, we wrote screenplays because we didn’t know what was the traditional method for a graphic novel.

Once the script feels strong, we move to storyboarding, followed by illustration, lettering, and final production. Our process is also iterative, something that we learnt in architecture school too, that the first draft is never the best.

Discussions on urban green spaces often stop at parks and street trees. Do you think we’re missing other important links, or should we be looking at green spaces differently?

Green spaces aren’t just parks or maidans, they’re everything that allows a city to breathe. In most Indian cities, small leftover spaces like road edges, wetlands, courtyards, terraces, even temple grounds often perform the ecological function of “green.” You don’t see them manicured like in Europe, but rather as big banyan or native trees towering over entire roads.

In our city itself, we have seen so many trees getting cut over the last few years just because it was a hindrance to a road widening or a new development or something else. But never as ecosystems of their own. Also, we feel like trees serve as important spaces in the city. The wide canopy of a banyan tree shading a vendor’s cart is as valuable as a park.

Most importantly, we need to rethink ownership and access. Green space shouldn’t always mean manicured, fenced parks available only to a select few. Sometimes the best green spaces are those that are slightly wild, collectively owned, and open to reinterpretation.

When dealing with complex topics like waste, sustainability, and urban mobility, how do you keep the message relatable without losing its seriousness?

At the core of Leewardists, is writing. Both of us are obsessed with storytelling that’s rooted in context. Our architecture education taught us that design must respond to where it belongs – the same rule applies to our scripts. We find that a lot of storytelling (which is very less) in the space of the built environment, whether it is a book on mobility, waste management, sustainability, is scarred with a superhero coming and saving, solving these issues but never simply talks about what is the issue in the first place.

We believe humour is not the opposite of seriousness; it’s often the best way to reach it. Our comics use humour as a cloak for critique but isn’t that how comics have always been and done to serve?

What are the biggest challenges in making urban mobility efficient while also being equitable and accessible to all residents?

Moving around in a city isn’t an equal experience. A woman, a child, a transperson or a person with a disability navigates the same city very differently. Sometimes, making systems efficient without equity may leave most of us behind. The other challenge is imagination.

Our planning still caters to a car-owning minority. We rarely imagine cities from the point of view of a pedestrian, a street vendor, people with disabilities or a parent pushing a stroller and many more.

Beyond infrastructure, how can cities influence people’s travel behaviour to reduce emissions effectively?

We truly believe that big changes in a city are often dependent on understanding psychological behaviours/patterns and cultural aspects of a city and providing solutions for that.

Cities can influence behaviour by designing systems that prioritize experience over efficiency alone. If taking the bus or walking becomes the most convenient, predictable, and even enjoyable way to move, people will change their behaviour. But that also requires changes in policy- subsidised public transport, shaded sidewalks, reliable first and last-mile connections and probably more solutions that an expert could say better.

(Published under Creative Commons from Mongabay India)