Analysing The History Of The Indian Ocean With Cruise Records, Sediment Cores

Dec 5, 2023 | Pratirodh Bureau

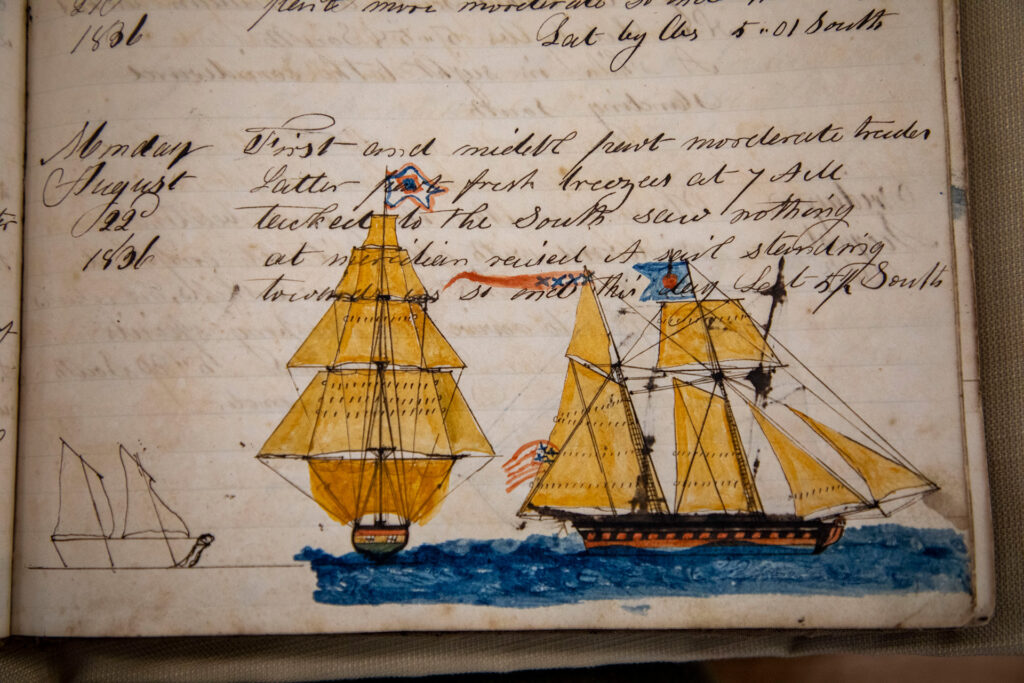

Whaling logbook at the Providence Public Library (Photo by Jayne Doucette/Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution)

Almost 150 years ago, Christmas, aboard the SMS Gazelle, a mid-sized German warship that circumnavigated the globe in the late 19th century, was a day of activity. The vessel’s naval officers and surveyors were recording temperature data in the southern Indian Ocean.

Combined with cruise reports of two other German expeditions, Valdivia (1898-1899) and SMS Planet (1906-1907), the relatively lesser-known vessels yielded over 500 temperature observations in the Indian Ocean at depths spanning from the surface to the seabed.

Physical oceanographer Jacob Wenegrat, who analysed the sub-surface temperature data of the three expeditions, says cruise reports are underutilised data sources. “These techniques have been proven with the 1870s Challenger ocean expedition’s data (that were used to infer 20th century warming and cooling in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans) and now with these German deep-sea expeditions,” he says.

Wenegrat’s team digitised the data from these three expeditions, making this historical information available to other researchers trying to unravel the complexities of ocean warming. These observations provide a first look at subsurface temperature change in the Indian Ocean over the 20th century.

The Indian Ocean plays a key role in influencing the Indian monsoon. The monsoon season forms the lifeline for millions of people’s water availability and agricultural activities. However, attention on the Indian Ocean has only been recent, while its Atlantic and Pacific counterparts are far better understood.

Historical records such as cruise records extend the available observational record back more than a century, providing important baseline data to study human-caused changes in the Indian Ocean as it warms rapidly, with far-reaching effects on weather and climate.

Researchers from several fields use the term ‘Anthropocene’ informally to refer to the current geological time interval, in which human activity is influencing Earth’s conditions and processes. This proposed new geological epoch, according to geologists, began when humans started altering the planet with various forms of industrial and radioactive materials in the 1950s.

“The Indian Ocean basin could be considered as a canary in a coal mine because changes that are now being observed in this ocean basin could also happen in other oceans,” states oceanographer Caroline Ummenhofer at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in the United States.

Ummenhofer mines climate clues tucked away in weather data logged by 19th century American whalers who also voyaged to the Indian Ocean. The New England whaling ship logbooks extend the knowledge of weather conditions over the oceans back to the early 1800s. “This long-term context is essential to understand what aspects of shifting wind and weather patterns observed today might be due to natural variability and which ones due to human-induced climate change,” she adds.

This distinction has important implications for climate risk assessments for vulnerable Indian Ocean rim communities because how one prepares for changes in the monsoons or storm impacts along the coast, for example, will look different when one anticipates conditions to be adverse only for a few years or a decade before reverting again due to natural variability.

“Instead, when we know to expect a trend of progressively worsening conditions and increased climate risks for decades to come, communities need to prepare quite differently,” she says.

Scientific Interest In The Indian Ocean

Although the Indian Ocean was recognised by Europe as a vital maritime trade route among Asia, Africa and Europe since ancient times and for its strategic significance during the Age of Exploration and colonisation, Panchang says it was the emerging connections between the nourishing monsoon and natural resource bounty in the Indian Ocean basin that encouraged researchers to systematically and collaboratively explore the ocean.

The 13-country International Indian Ocean Expedition (IIOE) from 1959 to 1965, became the first comprehensive oceanographic effort dedicated to the Indian Ocean. The organiser, Special Committee on Oceanic Research (SCOR), stated the Indian Ocean as ‘the greatest unknown in the global ocean.’

The IIOE carried out oceanographic (including phytoplankton and zooplankton sampling) and meteorological studies across the basin, laying much of the scientific foundation for the modern understanding of the Indian Ocean. It also led to the birth of the Indian Ocean Biological Centre, Goa, which evolved into the National Institute of Oceanography (NIO).

Subsequent multilateral efforts, such as the Indian Ocean Experiment (INDEX 1979) and the Deep Sea Drilling Project (DSDP) (1968–1983), built up on the work of IIOE over the next 50 years.

As part of the DSDP, the drilling vessel Glomar Challenger first conducted ocean core drilling (excluding offshore hydrocarbon exploration/exploitation) in the deep waters of the Indian Ocean in 1972, at designated sites in the Bay of Bengal, the eastern Indian Ocean, and the Arabian Sea, says marine geoscientist S. Rajan, a former director at India’s National Centre for Polar and Ocean Research.

“These initial exercises were, strictly speaking, not Indian efforts but formed part of the DSDP. The early drilling activities were motivated by the desire and need to understand the geological and oceanographic histories of the Indian Ocean, such as the development of the Bengal and Indus Fans,” says Rajan.

The Bengal and Indus Fan are two of the largest accumulations of sediments in the marine realm built by monsoon runoff from the Indian landmass, and the Himalayas. “These sediment deposits record a high-resolution history of varying rates of erosion and deposition, which can be linked to climate fluctuations through time,” he adds.

Geological records from DSDP’s successors, the Ocean Drilling Program, Integrated Ocean Drilling Program, and the most recent International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP) (2013-2023), furthered knowledge of paleoclimate, paleoceanographic and sea level changes in the basin. The IODP saw the first deep-sea drilling project proposed and carried out by India as a lead partner during March-May 2015 in the Arabian Sea.

As the impacts of increasing anthropogenic stress and global climate change became more prominent, the need to understand and predict changes in the Indian Ocean spurred the start of the International Indian Ocean Expedition-2 (2015-2020). It addressed contemporary science questions, such as ‘How can human-induced ocean stressors impact the biogeochemistry and ecology of the Indian Ocean?’ or ‘How are these impacts affecting human populations?’

The second edition also reflected the changes in ocean science and technology, integrating satellite observations, real-time measurements from ocean observation systems and ocean modelling, and improvements in computing and communication technology.

Ocean science requirements also spurred technological developments in seabed and sub-seabed sampling. It was in the late 1940s when Swedish oceanographer Borje Kullenberg made significant refinements to the traditional piston corer design, enabling the extraction of longer mud cores. “This innovative technique was pivotal, as it laid the foundation for conducting such studies,” says science historian Christoph Rosol, head of Anthropocene Formations at Max Planck Institute for the History of Science.

Sediment samplers such as grab, box corers, gravity piston and vibracorers are now routine in geoscientific investigations in and off the Indian waters. For more specific needs of the Indian scientific community, the Chennai-based National Institute of Ocean Development (NIOT) under India’s Ministry of Earth Sciences has crafted state-of-the-art samplers and corers, adds Rajan.

Setting Up The Anthropocene

The middle of the 20th century also saw the fusion of isotope geochemistry and oceanography, heralding modern, ocean-based paleosciences. Isotope geochemistry is the study of the relative and absolute concentrations of the elements and their isotopes in samples from the Earth and solar system.

According to Rosol, isotope geochemistry has blurred the lines between geophysics, geochemistry, and geology and given us a clearer understanding of the significant and transformative shifts our planet began experiencing in the mid-20th century.

In June this year, researchers proposed Crawford Lake in Canada as the official site marker for the start of the Anthropocene. The lake’s sediments capture chemical traces of the fallout from nuclear bombs and other forms of environmental degradation.

Georg Schafer, who, with Rosol, was part of the research team that proposed the official Anthropocene marker site, said when the Anthropocene discourse started, for the first 10 to 15 years, it was hard to make the public understand what it meant.

“But with the planetary situation changing in the last decade, people can see the Anthropocene impacts wherever they look. An Anthropocene landscape is highly artificial and it can only be kept up in its current state by the interplay of several fossil resources,” he adds.

Oceanographer and micropaleontologist Panchang, who is looking at ocean acidification in the Arabian Sea and unravelling how recent trends of ocean acidification are different from historical trends, emphasises the need for extracting sediment cores from undisturbed sites close to coasts to gauge anthropogenic impacts. “Ocean sediments record continuous deposition in coastal areas with a change in characteristics of constituent microfossils, minerals and proxies. Increasing human encroachment is endangering these archives,” reveals Panchang.