Obituary: Madhav Gadgil – A Scientist, Mentor And Institution Builder

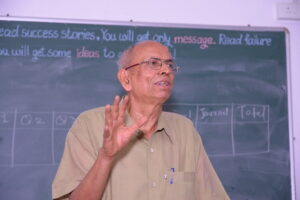

Madhav Gadgil at a school in Kasargod, Kerala, which he visited as part of a national environmental awareness programme (Image by Harish Vasudevan via Wikimedia Commons)

- India’s eminent ecologist and conservation biologist Madhav Gadgil died on January 7 at 83 in Pune, Maharashtra.

- Gadgil founded the Centre for Ecological Sciences in Bengaluru, and chaired the Western Ghats Ecology Experts Panel, which recommended the demarcation of ecologically sensitive areas within the Western Ghats.

- He mentored several leaders in ecology and conservation, like R.J. Ranjit Daniels and Jayshree Vencatesan.

India’s eminent ecologist Madhav Gadgil died on January 7. He was 83. His son Siddhartha Gadgil announced the death through a message to all those who had known and worked with Gadgil. His wife, Sulochana Gadgil, had predeceased him in July 2025.

Gadgil died in his home city Pune in Maharashtra. He had done his Bachelor’s from Fergusson College in Pune and Master’s from Mumbai University. He went to Harvard for his Ph.D. on mathematical ecology and fish behaviour.

However, Gadgil did not restrict himself to being a purist academic, but also wanted to learn from the field and use his knowledge for the benefit of people and communities. His initial work involved the studying of sacred groves in the Western Ghats, after which he moved to studying forest and environment policies. In more recent years, he had become widely known for chairing a panel on the conservation of the Western Ghats.

In a post on X (formerly Twitter), former environment minister Jairam Ramesh described Gadgil as a “top-notch academic scientist, a tireless field researcher, a pioneering institution builder, a great communicator, a firm believer in people’s networks and movements, and a friend, philosopher and guide to many for over five decades.”

Historian Ramachandra Guha, who had co-authored two books with Gadgil, summarises his unique qualities as a deep knowledge of his land and its people; profound intellectual originality; courage to oppose intellectual fashion; the ability to unite intellectual and practical agendas; strong democratic instincts; and an absence of cynicism.

Raghavendra Gadagkar, who has worked with Gadgil at the Centre for Ecological Sciences (CES) at the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, said: “Madhav Gadgil did pioneering work in life-history evolution under the mentorship of E.O. Wilson and William Bossert at Harvard University, as a Ph.D. student. Returning to India, he rose to become India’s best-known ecologist and conservation biologist and founded the CES.

“Appreciation and conservation of nature was a way of life for Madhav Gadgil. He was deeply in love with the Western Ghats, its plants, its animals, its birds, its people, and its hills, and strove during his entire life to bring appreciation and respect to them.”

Confidence in democratic institutions

Though Gadgil’s contribution to ecological studies in India is enormous, he had become a household name because of the recommendations of the Western Ghats Ecology Experts Panel (WGEEP) submitted to the Ministry of Forests, Environment and Climate Change in August 2011. The panel, chaired by Gadgil, had recommended that the entire Western Ghats mountain chain be declared as an ecologically sensitive area. However, due to impracticalities in such a classification, the panel had suggested demarcating ecologically sensitive zones (ESZs) within the Ghats.

With state governments and local communities registering their reluctance and opposition to the demarcation of ESZs, the panel report has become the topic of much polarised discussions in the Western Ghat states. What was forgotten, in all the acrimony that followed, was the recommendation of the panel to carry out this process of zoning democratically, with the involvement of the local self-government institutions such as the biodiversity management committees in the villages and urban areas.

Known for his excellent science and blunt articulation, Gadgil created a controversy in 2022, with his statement that the Wildlife Protection Act was anti-people and anti-constitutional. Environment lawyer B.J. Krishnan, who was a co-panelist in the WGEEP, said that though Gadgil was a “thoroughbred scientist, he promoted community-centric conservation that helped and enhanced the local livelihoods.” This is the guiding principle that reflected in his democratic approach towards the conservation of the Western Ghats and his strong views on the Wildlife Protection Act.

Krishnan remembers how Gadgil always had an abiding interest in the Western Ghats. He was involved with the movement to conserve the Silent Valley rainforests from being submerged under the reservoir of a hydroelectric dam in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Between November 1987 and February 1988, a group of environmental activists and citizens undertook the Save the Western Ghats March, which culminated in a meeting in Goa. At the meeting, Gadgil suggested that the march should result in a people’s movement to conserve the Western Ghats.

It is this spirit that got Gadgil involved in a meeting organised in Kotagiri in the Nilgiris district, Tamil Nadu, in 2010, in which Jairam Ramesh had participated. This meeting resulted in the formation of the WGEEP. The untiring efforts of the panel led to the panel report which, according to Krishnan, was unparalleled in style, substance and depth.

Institution builder and mentor

Madhav Gadgil initiated the ecological research that led to the establishment of the CES in 1983. It was the first centre of excellence established by the then Department of Environment (which later grew into the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change). Over the next few decades, the CES did path-breaking ecological research and also groomed students who went on to become leaders in their own right.

Ecologist R.J. Ranjit Daniels remembers him as the lead mentor for all those who came to study at the CES. Daniels joined Gadgil as a project assistant in 1983, helping his study of human impacts on biodiversity in Uttara Kannada district of Karnataka. In 1985, when CES called for Ph.D. students for the first time, Daniels applied and was selected under Gadgil’s guidance to study the birds of Uttara Kannada.

“Gadgil’s unique quality was that he was very open to new ideas,” said Daniels. “Even though he always brimming with ideas of his own, he never thrust any down the throat of his students. While he expressed his views strongly, he was open to others contradicting him.”

He encouraged his students to think independently. “Every time I had a new idea, I used to go to him with it. He used to listen to me patiently, and then pull out a paper or book from his personal library and asked me to read it. I learnt more and could polish my idea,” remembered Daniels.

Jayshree Vencatesan of the Care Earth Trust, who continued to receive mentorship from Gadgil even after she had completed her formal education, remembers him to be open to even diametrically opposite schools of thought. “On one hand, he would be guiding students on mathematical ecology, while also discussing traditional knowledge.”

He was also open to his ideas being used by others without attribution, as long as they delivered results. After the publication of the WGEEP report, Gadgil’s name became anathema to many state governments that had the Western Ghats running through them, for keeping aside areas for conservation is not an idea that administrators like. However, Vencatesan’s organisation could get policy action implemented by anonymising the ideas in their reports.

Gadgil was a recipient of multiple national and international awards and he was elected as a fellow in various academies of science. He received the Padma Bhushan in 2006. In 2021, a new species of plant from the Nelliyampathi hills of the Western Ghats was named in Gadgil’s honour — Elaeocarpus gadgilii.