Microplastics In Bhopal Wetland Spark Concern About Water Security

Oct 9, 2025 | Pratirodh Bureau

Plastic pollution along the shores of Bhoj wetland in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh (Image by Manish Chandra Mishra/Mongabay)

- A recent study finds evidence of microplastics in Madhya Pradesh’s Bhoj wetland, a Ramsar site that provides drinking water to about 40% of Bhopal’s residents.

- The study attributed the microplastic contamination to tourist and fishing activities, effluents from sewage treatment plants, commercial establishments and atmospheric transport.

- Experts call for more in-depth studies, a nationwide database on micro- and nanoplastics, and monitoring tourism activities, and setting checkpoints to stop sewage discharge and unregulated waste disposal.

A new study provides evidence of microplastics in the Bhoj wetland, a Ramsar site and Bhopal’s primary source of drinking water.

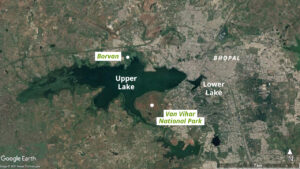

The Bhoj wetland spans nearly 32 square kilometres in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, comprising the upper lake (Bada Talab) and the lower lake (Chhota Talab). It is recognised as a Ramsar site of international importance and provides drinking water to about 40% of Bhopal’s 2.5 million residents, apart from supporting fisheries, agriculture, tourism and biodiversity.

As part of the research, Surya Singh and her colleagues at the Indian Council of Medical Research–National Institute for Research in Environmental Health (ICMR–NIREH), Bhopal, collected samples of the surface water. They analysed them to identify plastic particles larger than about 300 micrometres, using the Attenuated Total Reflectance–Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR–FTIR) method. They detected concentrations of 2.4 items per litre in the upper lake and 6.6 items per litre in the lower lake.

To put this in perspective, the findings suggest that Bhoj wetland’s microplastic levels are comparable to or higher than the most polluted stretches of the Ganga river, where concentrations have ranged from about 100 to over 1,000 particles per cubic metre or per 1,000 litres in some areas. By contrast, European freshwater lakes such as Balaton lake typically show much lower concentrations, often below 10 particles per cubic metre or 1,000 litres, highlighting that the Bhoj wetland’s contamination is far greater than most European systems and comparable to India’s worst-affected waters.

Singh cautioned that these numbers likely underestimate the accurate scale of contamination because the method used to detect the particles, ATR–FTIR spectroscopy, has a detection limit of around 300 micrometres. She said that if more advanced instruments such as Pyr GC-MS, µFTIR, or µRaman spectroscopy were available, they would have the capability to detect higher concentrations, and the findings would likely show higher concentrations of microplastics. The study was published in February this year in the journal AQUA — Water Infrastructure, Ecosystems and Society.

The team used the grab sampling method to collect the samples from different locations in the lakes and wetland. Other widely used sampling methods, such as neuston nets, are limited by their mesh size as well as have the risk of contamination. So, grab sampling, where the water sample is collected from a single point, was more effective to use in this case, she said.

Although the hazard level was classified as “very low” or “low,” Singh said that this assessment was based on the current concentration of microplastics available. “The limitations in the study, such as a small sample size, single-time grab sampling and the limited detection ability of the ATR-FTIR method, also need to be considered.” The study also had other challenges such as maintaining a plastic-free environment, finalising the experimental protocol as there is no standard protocol available, analysis of obtained particles, and more, Singh noted.

Sources of microplastic pollution

The study attributed the presence of plastics to four main pathways — tourist and fishing activities, effluents from sewage treatment plants, commercial establishments and atmospheric transport. Singh recommends that the practical interventions that local authorities can implement could include strict observance of the ban on single-use plastics in tourist sites (although it is already banned since 2022), public awareness and behaviour change campaigns, enhancing infrastructure for waste collection etc. “Systemic policy changes may include implementing extended producer responsibility (EPR) for plastics rigorously (although it is already in place since 2022), mandating microfibre filters in washing machines, integrated watershed management policies etc.,” she suggested.

Why Bhoj wetland matters for Bhopal

According to the District Environmental Plan for Bhopal, the upper lake, Bada Talab, supplies about 40% of Bhopal’s drinking water and the wetlands support biodiversity including fish and migratory birds. Any threat to its water quality therefore has cascading implications for human health, livelihoods, and ecological balance. Even low concentrations of microplastics could accumulate in sediments, be ingested by aquatic organisms, and ultimately reach humans.

Another 2025 study by Dinesh Kumar Gupta and colleagues examined six major waterbodies in Bhopal, including the upper and lower lakes in Bhoj wetland, Shahpura, and Kaliyasot, across three seasons. They found microplastics at every site, with concentrations ranging from about 540 to 1,410 particles per cubic metre. Fibres, mostly nylon and polypropylene, made up nearly 90% of the particles, and most of them were 75-600 micrometres in size, small enough to be ingested by fish. Even at “low to medium” levels compared with global studies, the researchers warned that microplastic pollution is persistent and increasing.

Together with the Bhoj wetland study, these findings show that microplastics are already widespread in Bhopal’s waters and could intensify without stronger safeguards.

While marine systems have received considerable attention, inland freshwater systems remain understudied in terms of analysing microplastic presence. Apart from isolated work on rivers like the Ganga, only a few studies exist.

When asked about the safety of the city’s drinking water, Varun Awasthi, the Additional Commissioner of the Sewage and Water Division at Bhopal Municipal Corporation, told Mongabay India that the corporation ensures proper treatment before supplying it. “We have modern treatment facilities in place and a dedicated laboratory to monitor water quality,” he said.

Need more activity monitoring and in-depth studies

B. K. Das, the director of the ICAR–Central Inland Fisheries Research Institute in Kolkata, has studied microplastic pollution in India’s freshwater systems for many years. Talking about the reported concentration of microplastics, Das, who was not part of the Bhoj study, pointed out that in India, there are currently no standards for judging the toxicity of polymers such as PVC in drinking water.

While noting that Bhoj wetland is a primary source of drinking water, Das said that stricter safeguards are needed. “Monitoring and managing tourism activity, setting checkpoints to stop sewage discharge and unregulated waste disposal, and expanding public awareness campaigns on the health and ecological risks of plastic pollution, is important,” he said.

Das also emphasised the need for in-depth studies to establish how different types and levels of microplastics affect aquatic organisms.

Another independent expert, Abhijit Sarkar, an assistant professor at the Department of Botany at University of Gour Banga, West Bengal, spoke about the study design saying, “Our own research on similar issues in local contexts suggests that results can vary significantly depending on factors like microplastic sources. Without more information on the sampling site, it’s challenging to conclude. I agree that ATR–FTIR has limitations, particularly in detecting nanoplastics. However, it remains a reliable technique for microplastic detection.” He also stated that “the current low risk may not necessarily imply future safety.”

Sarkar also stated that the government should prioritise creating a nationwide database on micro- and nanoplastics. “In fact, the CPCB might consider including it as a major criteria pollutant. We’re also exploring mitigation strategies for this issue.”

Meanwhile, for Singh and her colleagues at ICMR–NIREH, the next priority is to study sediments, benthic organisms, and potential food-web transfer of microplastics, aligning with the institute’s broader mandate on researching emerging pollutants and health risks.

(Published under Creative Commons from Mongabay India)