Ways In Which Tiger Conservation Safeguards India’s Water Future

A tiger crosses the Ramganga River in Corbett Tiger Reserve, Uttarakhand. In 2017, WWF reported that the reserve’s forested catchments along the Ramganga provide crucial water services to downstream areas in Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh (Image by Mayank Jaiswal)

- Protecting tiger habitats safeguards natural watersheds that supply freshwater to millions of people and vast agricultural areas across India.

- Recent documentation shows that 53 tiger reserves help maintain several rivers and streams.

- With growing water stress resulting from climate change, population growth, and industrialisation, expanding and managing tiger habitats sustainably can help secure India’s freshwater systems and ecological resilience, writes the author of this commentary.

A British collector of Tirunelveli (then Tinnevelly), R. K. Puckle, had warned in the late 19th century that the large-scale clearing of forests in the Kalakkad region would cause the Tamirabarani river to lose its perennial flow. About a century later, his warning came true. The Tamirabarani, the main source of drinking water and irrigation for the Tirunelveli and Thoothukudi districts, has begun drying up occasionally. Then, in 1988, the government of India declared the Kalakkad-Mundanthurai area a tiger reserve. The river regained its perennial status again, according to media reports.

This one example highlights the co-benefits of tiger conservation efforts. Though India’s tiger conservation strategy focuses on recovering the wild tiger population, which serves as an umbrella species. However, protecting tiger habitats, which encompass forests, rivers, wetlands, and grasslands, ensures the survival of numerous plants, prey animals, insects, and birds. These tiger habitats are also vital for clean water resources, benefiting both wildlife and local people.

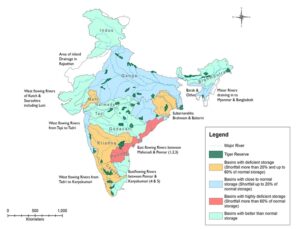

A book published by the National Tiger Conservation Authority (NTCA) and the Sankala Foundation, a non-profit organisation, in July 2025 documents the waterbodies to establish the connection between tiger conservation and water security. The conservation efforts in the 53 tiger reserves have contributed to enhancing water availability along 21,036 km of rivers and 33,248 km of streams within the tiger landscapes.

The book titled Stripes and Streams: Water Conservation in India’s Tiger Reserves mapped India’s tiger reserves and water bodies within them. Drawing from case studies, policy analysis and primary mapping of surface water in tiger landscapes, the book systematically explores the role of these water bodies in sustaining forests and wildlife.

It established that these reserves are also vital in delivering water services to approximately 340 million people and a large agricultural area covering around 19 million hectares across 18 states in India.

The forest-water nexus

In India, the forest cover constitutes 21.74% of its total geographical area. It controls streamflow, enhances groundwater recharge, and contributes to atmospheric water recycling, including cloud formation and precipitation through the process of evapotranspiration. Forests also function as natural filters, reducing soil erosion and water sedimentation.

India’s tiger habitats are primarily located within forests, which act as natural water catchments and critical watersheds for the country’s river systems, the book says. These habitats act as natural sponges, absorbing rainfall and recharging aquifers while preventing river sedimentation.

Based on its findings, the research highlighted the importance of water management in forest conservation. “As resources become more constrained and water demand grows ever greater, water management will be in the forefront of forest-related decision-making,” it said.

The water resource is shrinking. The country supports 18% of the world’s population yet has access to only 4% of global freshwater, making every drop precious. India’s water stress is compounded by population growth, industrialisation, and climate change.

The World Resources Institute’s Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas includes India among the 25 countries facing “extremely high” water stress. A 2018 NITI Aayog report said that the country’s water demand is expected to exceed the available supply by 2050, resulting in an estimated 6% decline in gross domestic product. Similarly, the National Commission for Integrated Water Resource Development estimated that India’s water requirement could reach 1,180 billion cubic metres by 2050. The current availability is 695 BCM. It will have an impact on the agriculture and food security of millions.

While the tiger population has seen a manifold increase over the last few decades, and the water crisis has deepened, both water and tiger conservation efforts in India have undergone significant evolution. Water conservation has moved from traditional community-led practices to large-scale infrastructure projects. It has now moved toward integrated, sustainable, and community-based approaches.

Similarly, India’s Project Tiger has evolved since its inception. In Phase I (1970s-1980s), the government’s focus was on creating protected areas to safeguard tiger populations. However, Phase II (1980s-1990s) witnessed a sharp decline in the number of tigers. It highlighted the need for stricter protection and scientific management. In response, Phase III (2000s–present) adopted a landscape-level approach that includes scientific monitoring, habitat restoration, and the creation of new reserves.

Launched in 1973 with nine reserves covering 18,278 km², Project Tiger has now expanded to 58 reserves, spanning over 84,487 km² across the country. These reserves are vital not only for protecting tigers and biodiversity, but also for conserving natural resources, such as water, which sustain both wildlife and people.

The study mapping major rivers that originate from tiger reserves underscores this link, showing that protecting tiger habitats is also key to securing India’s freshwater resources and supporting millions of people who depend on them.

Beyond the stripes

About 600 rivers in India originate from or pass through the catchment areas of tiger reserves, helping to regulate water flow by allowing rainwater to soak in, reducing surface runoff, and supporting river base flow during dry periods. Rivers such as the Godavari and Krishna, which originate in the forests of Central India, depend on forested catchments that overlap with various tiger habitats.

According to India’s 2022 population estimate, the Western Ghats are home to 1,087 tigers, making it one of the largest connected tiger populations in India. The Western Ghats are a mountain range that stretches 1,600 km along India’s western coast, approximately 30-50 km inland, traversing the States of Gujarat, Maharashtra, Goa, Karnataka, Kerala, and Tamil Nadu. These tiger habitats play a vital role in managing streamflow and water cycles in watersheds, including 16 rivers, mostly originating from Karnataka, such as the Cauvery, Nethravathi, Paalar, Bhadra, Varahi, Gundia, Kumaradhara, Seetha, and Kaali Rivers, which are essential for local and regional water security. These watersheds support the farming and drinking water needs of around 80 million people in southern India.

Conserving tiger landscapes is essential for ensuring the sustainable management of India’s water resources, which in turn help people ensure their livelihoods. For example, the Ranthambore Tiger Reserve in Rajasthan conserves water that benefits nearly 300 villages in an arid region of Rajasthan. Similarly, the Periyar River, which originates in the Periyar Tiger Reserve, supports the water requirements of Kerala and southern Tamil Nadu. A 2019 NTCA study estimated that the benefits related to water provision from 10 tiger reserves amount to over ₹330 billion annually.

In 2017, the World Wildlife Fund for Nature (WWF) reported that the forested catchments of the Corbett Tiger Reserve, along the Ramganga River, provide crucial services for downstream areas in Uttarakhand and Uttar Pradesh. From 1974 to 2010, a downstream dam generated significant economic benefits, including $41 million (₹3.64 billion as per the exchange rate on October 8, $1= ₹88.82) worth of electricity and 88,000 million cubic metres of irrigation water, without requiring direct investment in catchment treatment or major siltation.

India’s overall water demand is rising, with agriculture being the largest user, accounting for around 85% of the country’s total freshwater consumption. Indeed, investing in tiger conservation by protecting approximately 2.6% (about 84,487 km²) of the total land area has contributed to India’s water security. The country still has about 380,000 km² of potential tiger habitat outside the purview of Project Tiger. Bringing these potential tiger habitats under the umbrella of the Project Tiger will help safeguard river and forest ecosystems, which in turn could contribute to addressing future seasonal freshwater shortages in the country.

(Published under Creative Commons from Mongabay India)